In 1996, Reinhold Joest entered a WSC Porsche (an open cockpit prototype sports car) at Le Mans. The car was an unknown quantity never having raced before. Although simulations and calculations by Porsche indicated it might be favored over the GT1 class cars (cars based on road cars per the Le Mans rule set), it was unproven.

Porsche was hedging their bets for victory. They entered two Porsche GT1 models from Weissach and Reinhold Joest ran two prototype cars. Porsche had given him the cars to run, as everyone was unsure of what the best package for overall Le Mans victory was—Prototype World Sports cars or the GT1 class. The Joest-entered car won the race, and the same car won again in 1997. The genesis of this car is an interesting and somewhat strange story.

The Backstory of the TWR-Porsche WSC

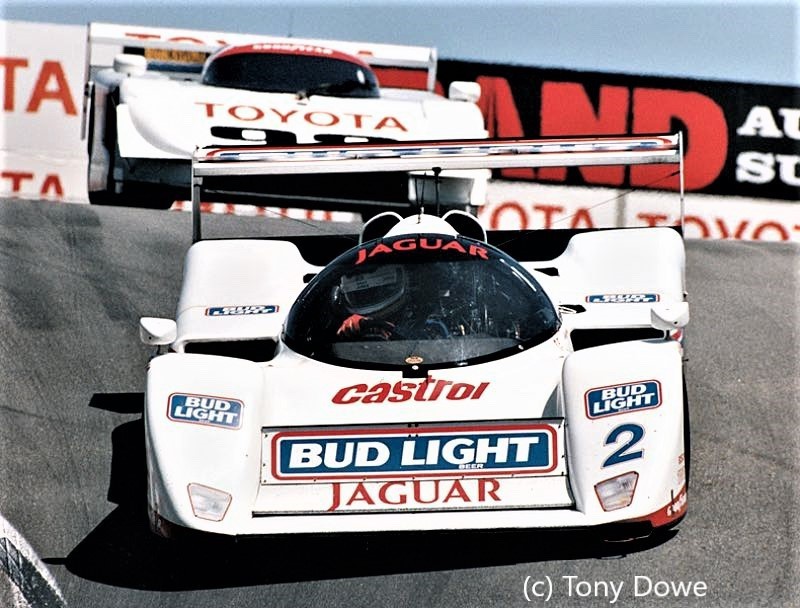

The story actually started several years before in 1990. Group C had been the basis for the World Sports Car Championship since 1982. Group C cars were prototype coupes such as the Porsche 956, 962, Sauber Mercedes, and Jaguar XJR-12.

It was a fuel-based sports car series. Fixed amounts of fuel were allowed per race. Large sums were spent by Mercedes, Porsche, Jaguar, Nissan, Toyota, Mazda, and others building and developing cars for this formula.

The FIA (Federation International d’ Automobile) began to realize that manufacturers were investing increasingly in the Group C concept to the detriment of other series. There seemed to be more interest in Group C and GTP than even Formula 1 from a manufacturer perspective.

Under the auspices of cutting costs and improving racing the FIA announced rule changes for Sports cars in 1990 to take effect in 1991. The new cars would be 3.5-liter normally aspirated cars. While the older cars were still grandfathered in for another year, the rules were structured heavily in the favor of the 3.5 cars.

Weights were increased for the older group C cars, severely hampering them in competition with the 3.5 cars. The 3.5 cars were made exempt from any fuel usage limits, while the older group C cars carrying increased weight struggled with fuel mileage. The races (except for Le Mans) were shortened to take away any advantage the older Group C cars might have in reliability.

Tom Walkinshaw Racing, which ran the factory Jaguar program, realized the old cars would be problematic for every race in 1991 except Le Mans. Walkinshaw then had a whole new car built for the new 3.5-liter formula.

The car was designed by a team consisting of Rory Byrne, John Piper, John McLoughlin, and aerodynamicist Mark Thomas. Project leader and technical director was Ross Brawn, who would eventually go on to be technical director of Ferrari in the Michael Schumacher era, as well as running his own F1 team in the 2000s. This car became the Jaguar XJR-14.

Jaguar being a Ford owned company, the engine used was the Ford Cosworth HB 3.5-liter V8. They qualified on pole at the first race in 1991 (Suzuka) by 4 seconds, but both cars dropped out with problems. But they did well enough in the other races to claim both the Teams Championship and Driver Championship (Teo Fabi) for World Sports Cars in 1991.

TWR had the luxury of running the V12 powered XJR-12 at Le Mans only, where all the 3.5 cars fell out or had problems, and Jaguar finished 2nd, 3rd, and 4th there with the XJR-12. The race was won by the Mazda 787B 4-rotor, due to a rules anomaly.

At the end of 1991, Jaguar decided to stop supporting the World Sports Car Championship. Several of the superb chassis were sold to Mazda, who continued in World Sports cars with an XJR-14 chassis with a Judd engine, rebranded as a “Mazda”. They had mixed success and then quit the championship after 1992 as well.

Jaguar was still supporting the IMSA series in the US in 1992, so several XJR-14’s were shipped over to Tony Dowe (TWR USA) for use in the IMSA series. The car was run in the short sprint races. It was frequently the fastest car but proved fragile and only won two of the races. There were issues with the wheels, which ended up most likely costing two additional wins at Lime Rock and Elkhart Lake.

The IMSA spec car was making more downforce and the tracks (in the USA) were bumpier, causing wheel failures. New wheels subsequently solved the problem, but they ended up second in the championship to Toyota.

At the end of the season, IMSA announced that they would change rules to the new WSC formula (World Sports Car) starting in 1993 (and exclusively in 1994). Jaguar dropped out of IMSA, and the cars just sat in the TWR workshops in Valparaiso, Indiana.

The 3.5-liter FIA Sports Car Championship, in the meantime, was a complete flop, as there were no cars or manufacturers interested. The FIA and Le Mans quickly announced further rules changes moving to the “GT1” concept to utilize high performance road cars such as the McLaren F1-GTR and eventually the Porsche 911-GT1, which was a 911 based car, but mid-engined.

IMSA (International Motor Sports Association) meanwhile moved to a whole new rule set called WSC (World Sports Car). These were open cockpit, flat bottomed prototypes, powered by “stock block” based engines. The IMSA series gained traction in 1994 with the arrival of the Ferrari 333SP and subsequent building of Riley & Scott Mk 3 chassis, which could support a variety of engines.

Developing the TWR-Porsche WSC

Porsche racing at this time, was under the management of Max Welti. He had managed the Sauber-Mercedes program in Group C and would eventually go back to run the Sauber Formula 1 program later in the 1990s.

Porsche in the early 1990s really had no car to compete with. They had no new 3.5 car or engine to run in the WEC. And they had no IMSA WSC car either. They did, however, have the proven 962-based engine and a particularly good endurance gearbox.

For the 1994 Le Mans, Max and Norbert Singer came up with the plan to enter a “GT1” car. At that time, GT1 rules specified the car must be based on a road car. Jochen Dauer had been building a small number of road going Porsche 962-based cars. So basically, a 962 was used and called a Dauer-962 GT1.

The result was spectacular, with a 1st and 3rd at Le Mans in 1994. Porsche had pushed the rules to the limit once again (aka Porsche 935 Moby Dick). But the ACO (Auto club de l’ouest) and FIA (Federation Internatonale de l’Automobile) immediately closed that loophole for 1995.

In any case, Porsche knew the car was not viable going forward. Other manufacturers such as Toyota, Jaguar and Peugeot were using advanced Carbon composite chassis, which at this point Porsche had little experience with.

The Main Men Behind the Concept, Building, & Engineering of the TWR-Porsche

Alwin Springer (above) was the Director and CEO of Porsche Motorsport North America during this time in the 1990s. He was in favor of this project because he wanted a car Porsche could run in IMSA in 1995, as they had nothing other than GT cars.

Tony Dowe (above) was the General Manager of Tom Walkinshaw Racing in the USA. He was Responsible for running the Jaguar program in IMSA. He was tasked by Walkinshaw to either find a project his crew could work on or shut down the USA team.

Max Welti (above) was in charge of Porsche Motorsport at this time in the early 1990s worldwide. He realized Porsche had no car, extremely limited experience with Carbon Fiber chassis work, and, in fact, no experience. He had to sell this project to the Porsche Board.

The Head Porsche engineer at Weissach for Racing at the time was Norbert Singer (above). Once the board approved this project, Herr Singer would have to get involved in helping get this coupe with a Ford engine converted into a World Sports car with a Porsche Engine—not an easy job by any means.

An XJR-14 chassis with Porsche Running Gear

During Max’s ad hoc discussions with friend Tony Dowe of Tom Walkinshaw racing, some private brainstorming resulted in the idea to sell Porsche on using an XJR-14 chassis with Porsche running gear for Le Mans and IMSA events. This would be a car that could be completed rather quickly (in comparison to starting with a clean sheet of paper), or so they thought.

The idea would be to cut the roof off of the XJR-14 chassis and install the Porsche engine and gearbox in the car, thereby making it a WSC car.

Initially, this proved a hard sell at Porsche. Some were “shocked,”, while others thought Max Welti had maybe lost his mind. Possibly the only early supporter was Alwin Springer, who was manager of Porsche Racing USA. He realized Porsche had no car and had to do something.

The argument that Porsche had no car to run in 1995 in IMSA or Le Mans and was way behind in development of carbon chassis eventually held sway. Porsche R&D board member Horst Marchart (Max’s boss) gave approval for Max and Norbert Singer to travel to TWR in Indiana (USA) and meet with Tony Dowe to discuss the concept in mid-1994.

Alwin Springer had a good engine in the latest 962 based motor, designation 935/86, but no chassis to put it in. Tony Dowe (the manager at TWR in Indiana) had a chassis but no engine (the Ford Cosworth, being a race engine, was not IMSA legal in WSC). Tony asked Alwin for a loaner engine to try and stick in the XJR 14. They met at an IMSA race in mid- 1994 and came up with some logistics and plans to put the concept to the test.

The engine would be the 935/86 engine as run in the Dauer 1994 Le Mans car. Alwin provided an engine for mock- up and testing while discussions continued between TWR and Porsche.

Convincing the powers at Porsche—who had just spent almost 10 years battling tooth and nail with Jaguar in Group C—to now put their engines in Jaguar chassis was a tough order but eventually, everyone including Herbert Ampferer, and Wendelin Wedeking (Porsche CEO) were on board and a partnership was formed. Porsche Weissach viewed this as an IMSA and Le Mans project. The cars would run Daytona, Sebring, and LeMans in 1995.

Chief Engineer Norbert Singer at Weissach was in charge of the technical side for Porsche. He would make several trips to Indiana but was busy with other projects as well at this time. He would eventually send over some technicians and mechanics to help TWR with the construction and installations. The goal was to be ready by the 1995 Daytona 24 hours, continuing to Sebring and Le Mans.

Negotiations proceeded with Tony Dowe and TWR in Indiana and a deal was struck. The gist of it was that TWR would build the chassis, while Porsche would supply the drivetrain, some of the suspension, and the bodywork. Work would be completed in the second half of 1994 so that the car would be ready for the Daytona 24 hours in early 1995.

Tom Walkinshaw was very receptive to this project, as costs would now be shared, and he (Walkinshaw) would not be supplying the whole budget. The cars would be called TWR-Porsche WSC-95.

The TWR-Porsche WSC 95-01 & TWR-Porsche WSC 95-02

Two chassis were available, one brand new one, and one used one left over from the 1992 IMSA season. Work proceeded. Chassis 0691-01 would become TWR-Porsche WSC 95-01 and the new chassis would be designated TWR-Porsche WSC 95-02.

Work continued in Indiana during 1994—but of course, there were issues. Both sides most likely underestimated the work to build this car. Singer explained that it was more than just sticking an existing engine into an existing chassis. A lot of new components had to be developed and installed, including the aerodynamics (bodywork), gearbox pieces and installation, electric components, intercoolers, and radiators.

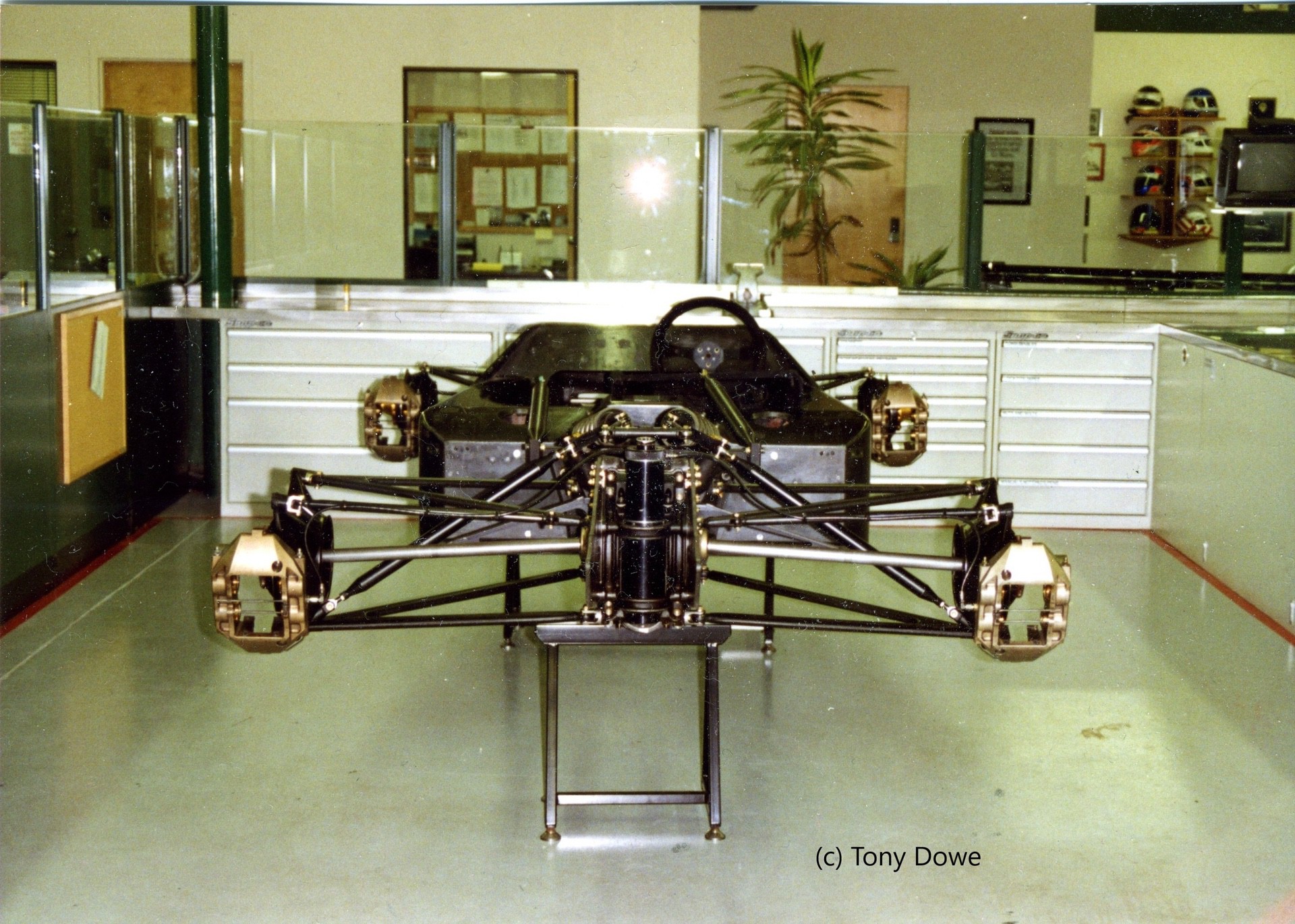

Most of the systems used in the XJR-14 had to be modified or redesigned. The XJR-14 had been a closed cockpit ground effect car, whereas WSC was an open cockpit, flat bottom car. The XJR-14 had used a 3.5- liter V8 engine; the new car would use the flat 6-cylinder turbocharged Porsche 3.0-liter turbo engine.

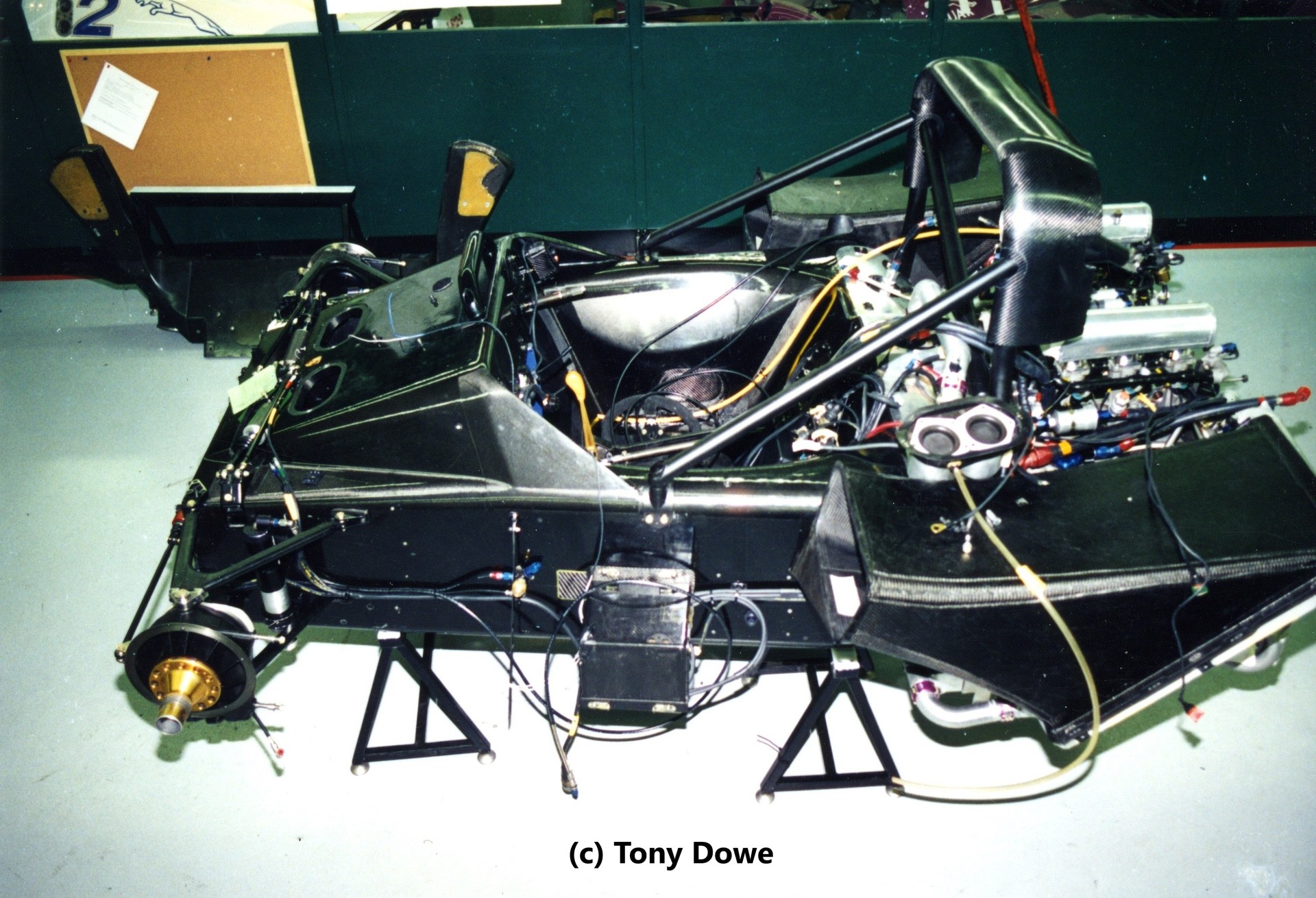

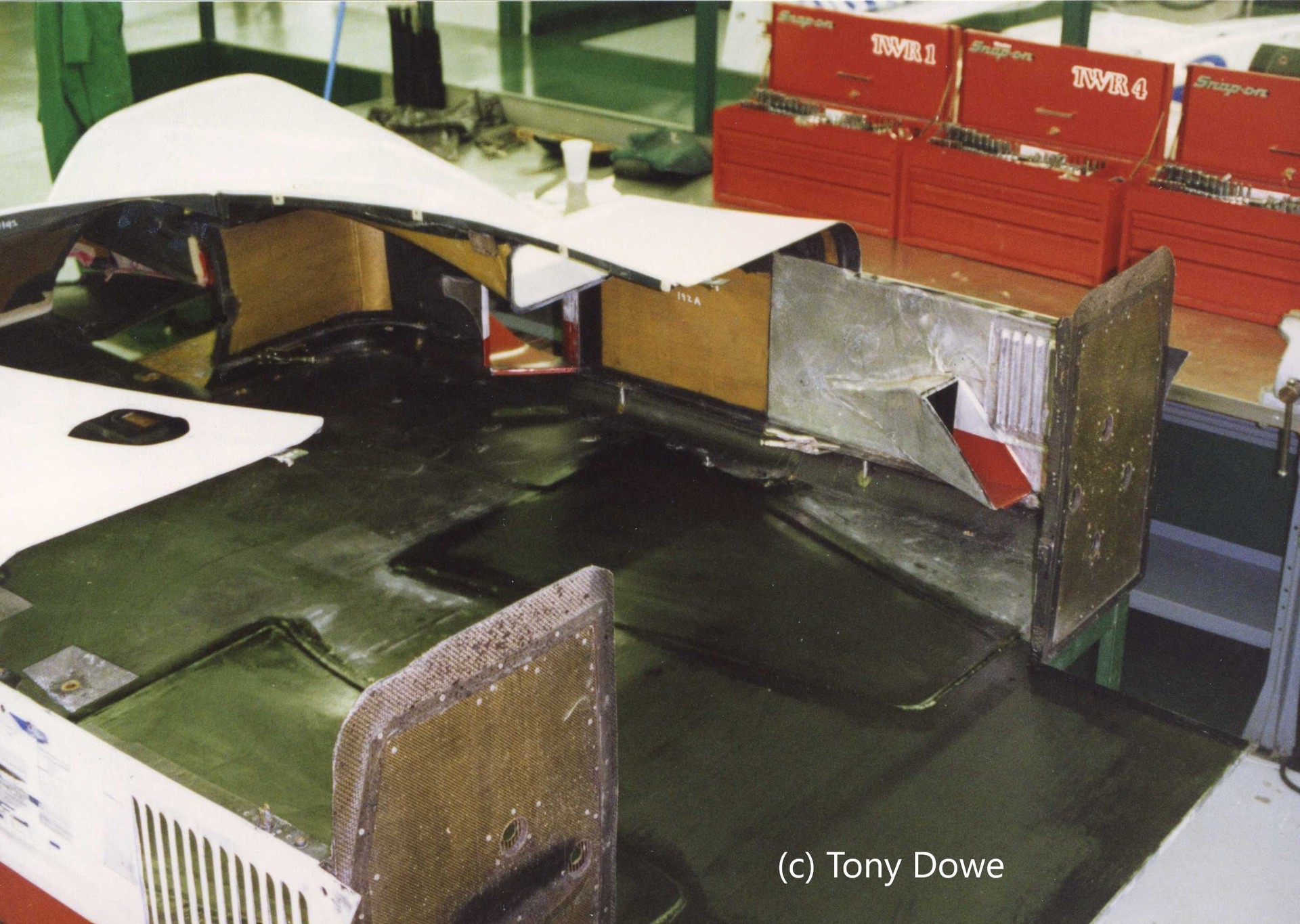

The Bare tub of the XJR-14 with the roof cut off and some suspension bits mounted sits in the TWR shops in Valparaiso Indiana in initial stages of construction in mid-1994.

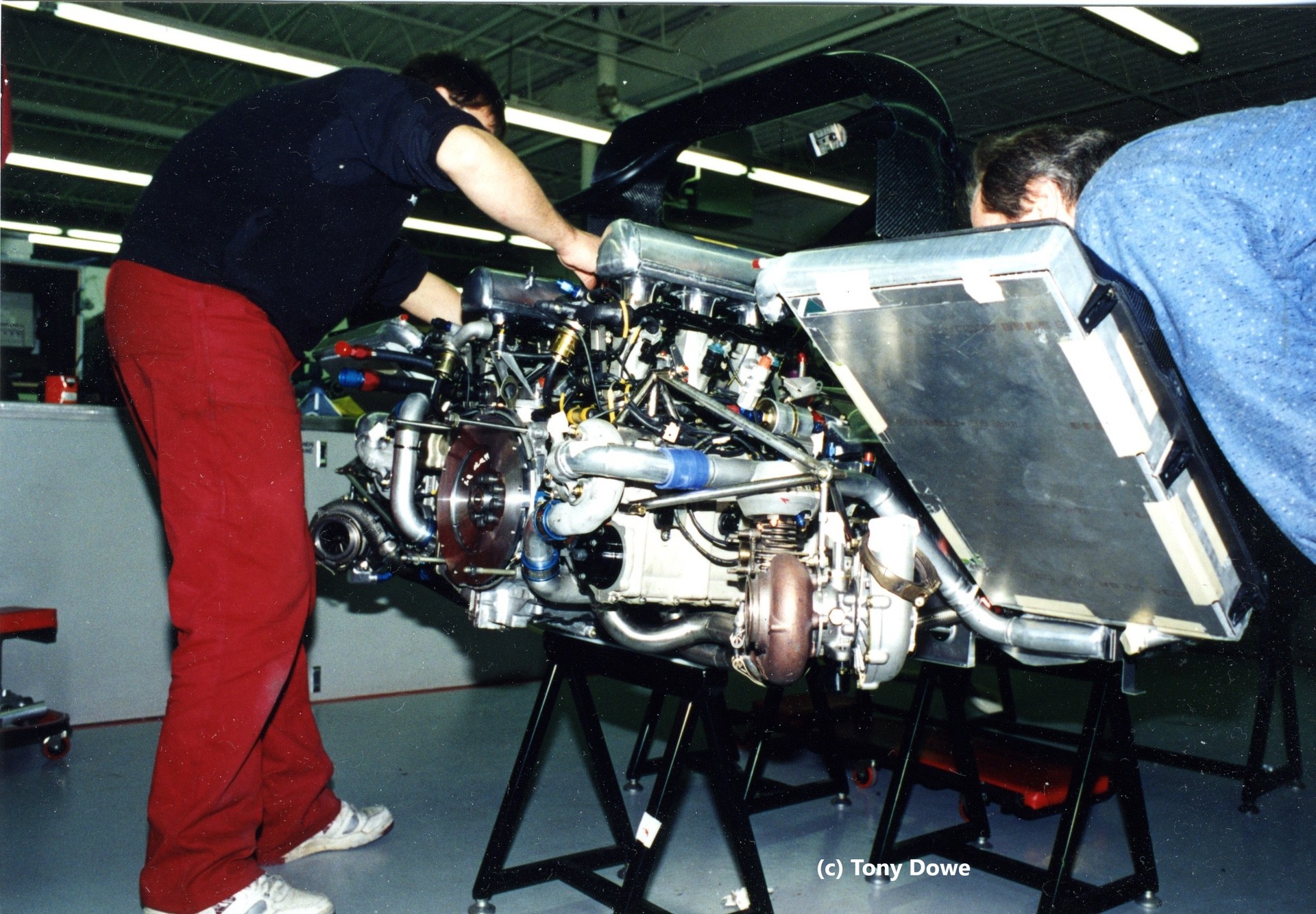

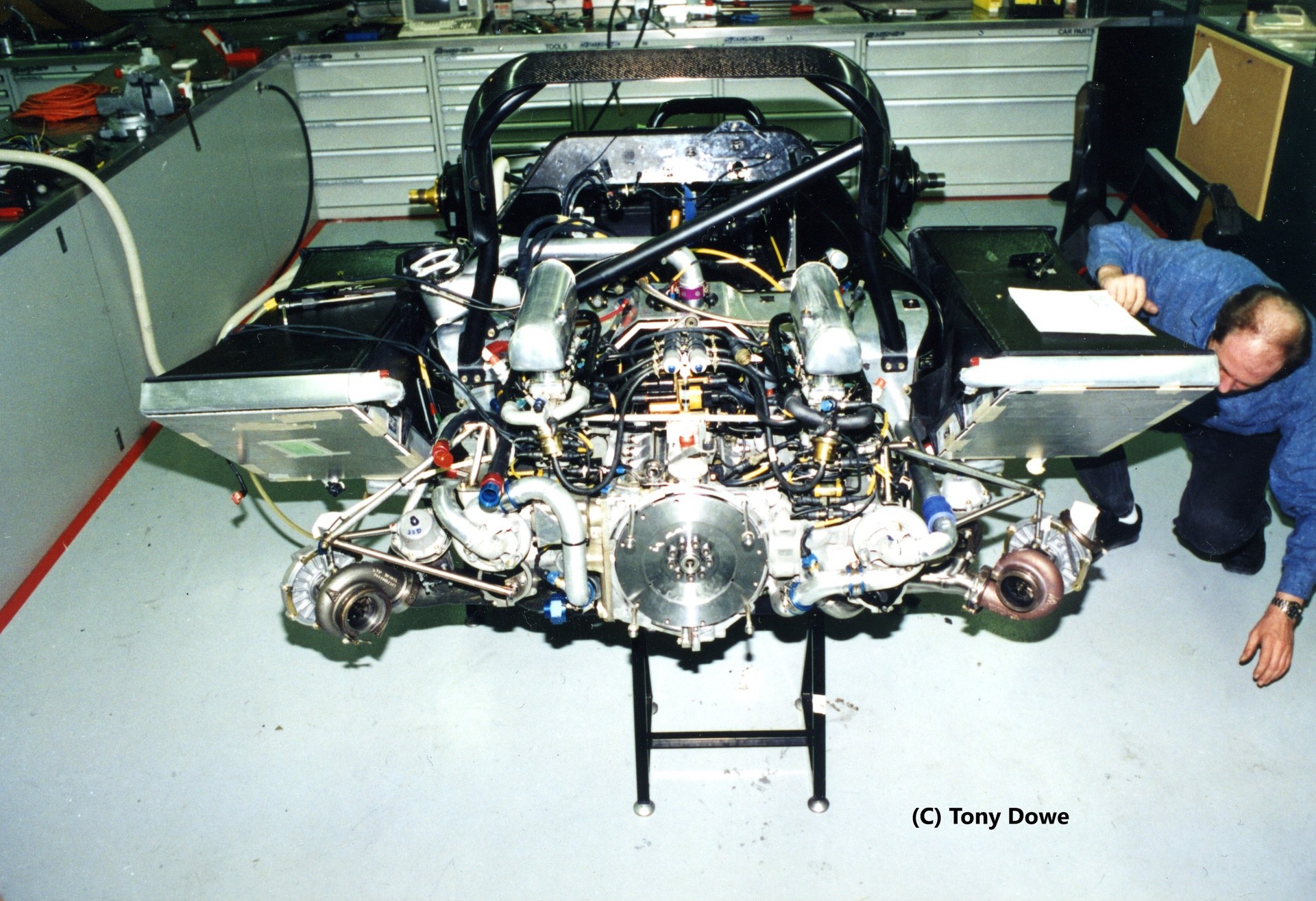

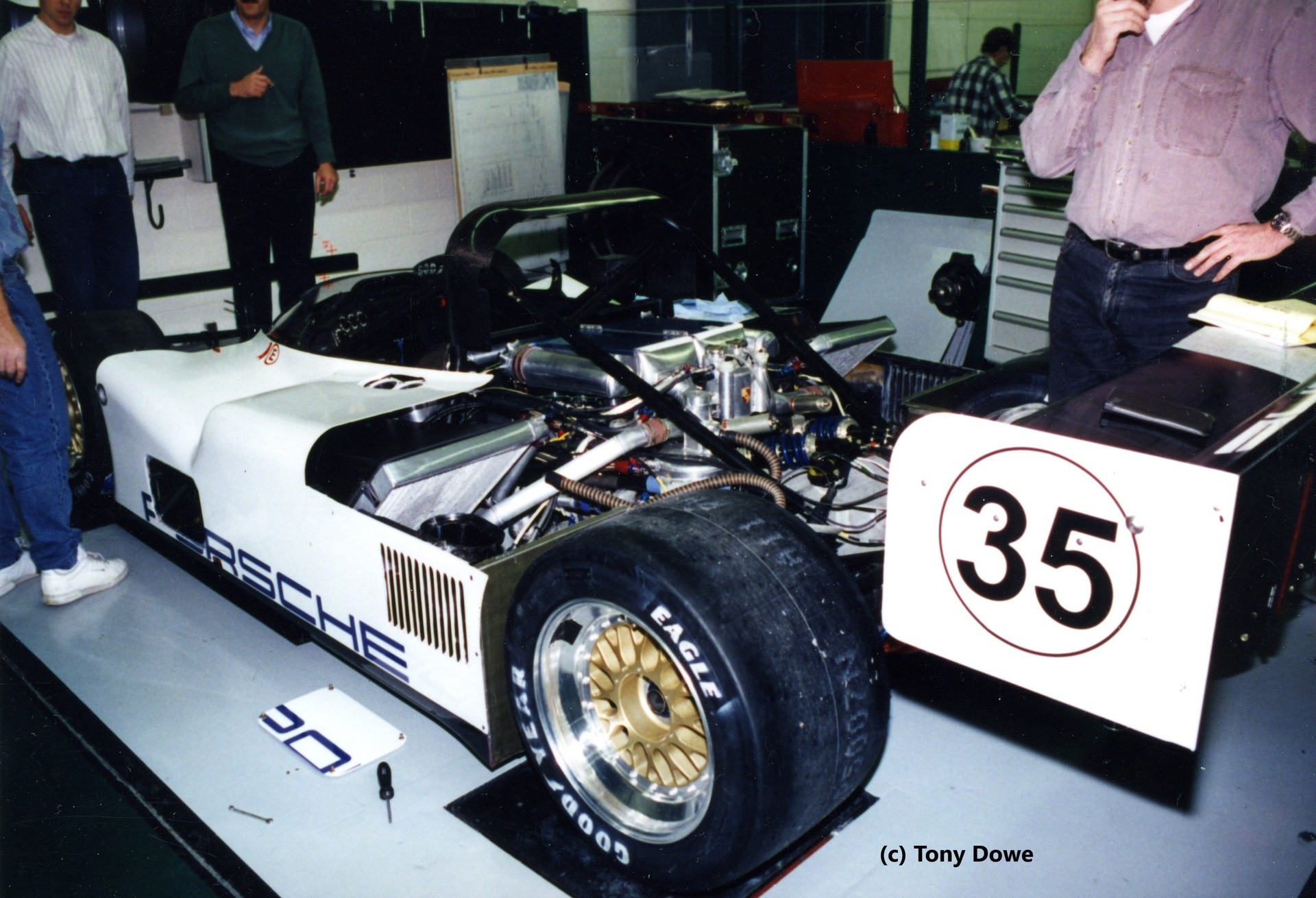

A 962 based engine was supplied by Alwin Springer for fitting tests. Here, TWR technicians work on fitting the Porsche 6-cylinder turbo with ancillary plumbing, radiators and other systems into a space originally designed for a Ford Cosworth V8.

Engine installed in the TWR-Porsche mid 1994.

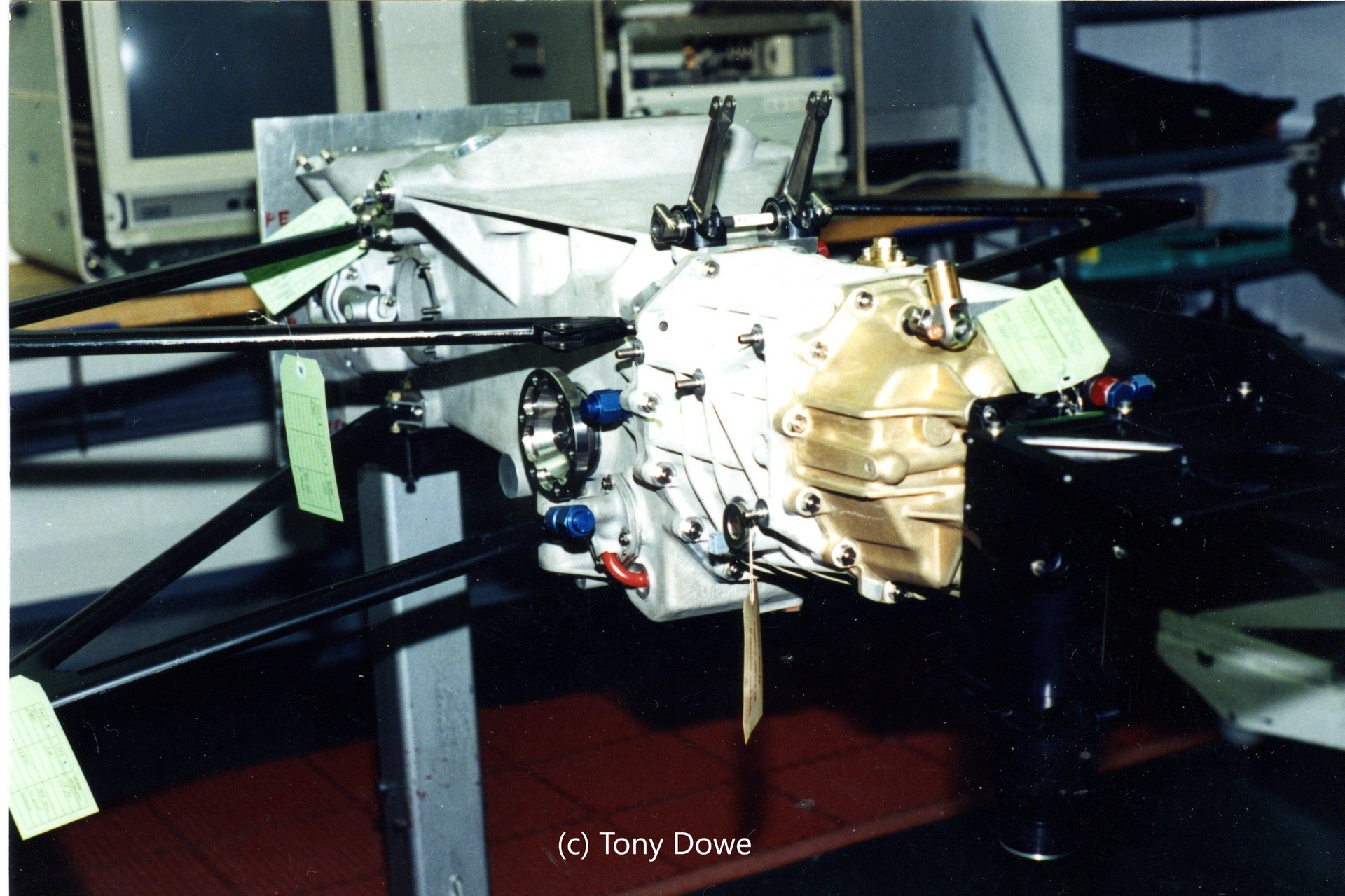

The engine bay was designed originally for the Cosworth V8, so some modifications would be necessary to fit the flat 6-cylinder Porsche engine in there. Tony Dowe related that the gearbox was a big issue. At first the XJR-14 box was going to be used, but it was a 3-shaft box and did not line up with the center line of the Porsche engine.

Plan B was to use the Porsche “962” gearbox. However, with that, getting the brackets to mount the rear wishbones would be very problematic. The gearbox did not match up well with the existing rear suspension.

On to Plan C: Ian Reed (The Jaguar Engineer in the USA) would redesign the XJR-14 gearbox with Porsche Internals. The case was to be made of magnesium to save weight. Tony found a company in Canada that would make the patterns and molds of five cases for $60,000 (a lot of money back then!).

Within 6 weeks, they had a gearbox in the car. The pattern shop of the Canadian company was near the Indiana shop in Illinois. As the cases were finished, Tony would send a man to pick it up, go to Chicago, and hand-carry it on the airplane to Germany for machining.

As the project went on, Tony realized time would be tight, and bearing tolerances in the gearbox would have to be exact as this was magnesium and not the normal Porsche Aluminum case. When it became clear that there would not be time to test the Magnesium box, Ian Reed (the Jaguar Engineer in the USA) had to work 48 hours straight and redesign the gearbox in Aluminum instead of Magnesium so the Porsche’s known bearing tolerances could be used.

Gearbox fitting proved problematic. Here are the initial stages of gearbox fitting with suspension components at TWR in Indiana.

The next issue to resolve were the driveshafts. On the XJR-14, Jaguar had used the then-new tripod drive shaft joints. Porsche had no experience with these and wanted to use standard 930 type CV joints.

In the spirit of teamwork and cooperation, a compromise was reached. As the gearbox was part of the drive line and Porsche’s responsibility, the gearbox side joints would be CV. On the outboard side, the existing tripod style was retained.

Of course, such drive shafts did not exist. Tony had to have them made at Metalore in California.

Chassis with engine and other components starting to take shape in mid-1994 at TWR. Much of the electrics, water system, and other plumbing needed re-design to accommodate the Porsche running gear.

Bodywork was re-designed as the car was now an open cockpit WSC car, not an IMSA GTP coupe. This took place in mid 1994 at TWR USA.

Bodywork being fitted at TWR in mid 1994. WSC cars by rule were flat bottom, so much of the original bodywork was not usable.

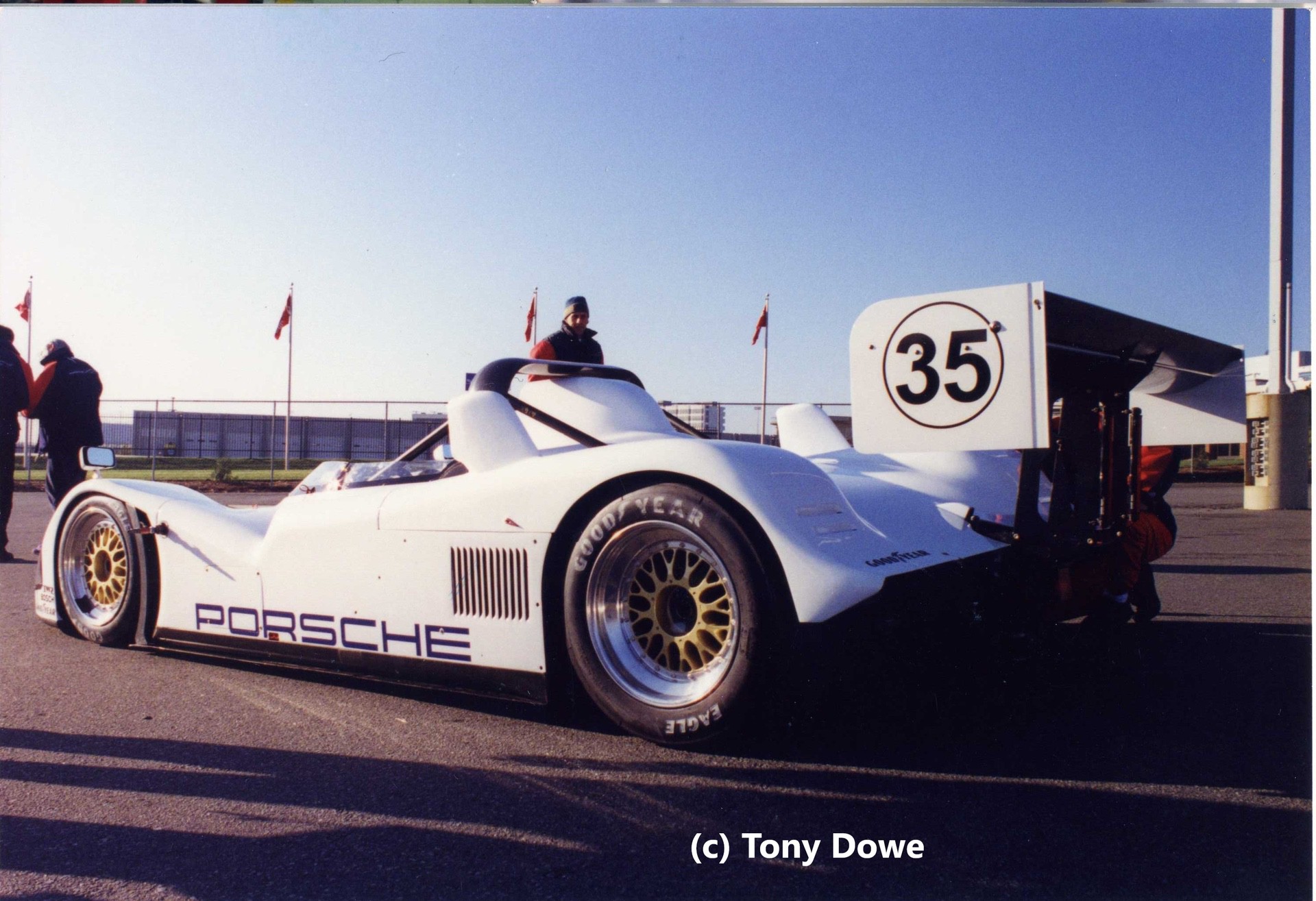

The complete car sits on the setup pad at TWR in late 1994.

Front view of completed car at TWR prior to Charlotte test in December 1994.

The Finished TWR-Porsche WSC

The collaboration between TWR and Porsche proved successful, and the two cars were built by the end of 1994. Porsche sent over some technicians to help. Walter Marelja and five main technicians were sent over from Germany for 6 weeks: Hans Eckert and Bertie Vogt were chassis specialists; Thomas Klein and Dieter Liebold were engine men; and Peter Rabus was the electrical specialist.

The cars were entered for the Daytona 24 hours in January 1995. The drivers would be the Andrettis (Mario and Michael), Hans Stuck, Thierry Boutsen, Geoff Brabham, and Scott Goodyear.

Testing the TWR-Porsche WSC

Having only just been finished, in December of 1994, the cars were taken to Charlotte Motor Speedway in North Carolina for a quick shakedown test prior to the ROAR (IMSA open test at Daytona) in early January.

As Alwin Springer recalled, it was not good. The drivers complained about the handling. The front end wandered. Porsche Engineer Norbert Singer came to the rescue with a solution. He realized there were aerodynamic issues.

The new IMSA regulations for WSC specified totally flat bottom cars, with no tunnels or diffusers allowed. The XJR 14 had, of course, run with ground effect tunnels in both the world championship of 1991 and in IMSA in 1992. Herr Singer realized more wind tunnel testing was needed, but his quick fix in the meantime was a wing change to balance the car, reducing drag in the process.

Mario Andretti, one of the drivers signed for Daytona, tests the car at Charlotte Motor Speedway in December 1994.

There was no time for any wind tunnel testing. First the cars had to go directly to the IMSA ROAR in early 1995. There, the car was some 2-3 seconds per lap slower than the quicker Ferrari 333SPs.

Hans Stuck, Geoff Brabham, and Thierry Boutsen stand with one of the two cars at the Daytona ROAR (test) in January 1995.

Testing at Daytona in early January 1995.

The car sits at Daytona in January 1995. Note the rear bodywork and wing. It would change in future years as the needed wind tunnel work was done.

Ferrari then complained to IMSA, saying the guarantee (for them to commit to the IMSA series) had been no turbos and no rules changes for a fixed time period. Ferrari also claimed Porsche was sandbagging (going slow on purpose pre-race so as to not show their hand).

Porsche complained that Ferrari were sandbagging and were already 2-3 seconds a lap quicker. The 333SP had debuted in 1994 and had a full year of IMSA competition under its belt. But the Ferrari did not run the Daytona race in 1994, so there was no real history of what the car could do there either.

There was a letter to Ferrari from IMSA in 1993, to the effect that there would be no rule changes and no turbos, written by then-CEO Dan Greenwood under the ownership of Mike Cone. The problem was that Mike Cone had sold IMSA to Charlie Slater by 1994, and the new CEO was Hal Kelley—who was a Porsche Fan and wanted them in the series.

In late 1994, Mark Raffauf and Hal Kelley of IMSA had flown out to Reno (Nevada) to meet with Porsche USA (Herbert Ampferer and Alwin Springer). Porsche explained what they were doing with this car. Hal Kelley gave a contingent OK.

But after the ROAR test in early January 1995, IMSA did some internal reviews of documents and the data collected at the Daytona test. The WSC rules were changed (by IMSA) to allow turbos but mandated a specific turbo and a fixed boost rate. Weight was also added to any turbo cars.

The rules changes were not well received at Porsche. Just after the Daytona test (two weeks before the race), Herr Wedeking made the decision to pull the plug on the project and withdraw the cars from Daytona.

There was turmoil at Daytona, as programs and press materials now had to be redone just two weeks before the race. There was also turmoil for poor Walter Marelja of Porsche. As he was boarding his flight in Stuttgart for Daytona, he was called from the factory and told to get his luggage off the plane and come home. The Project was cancelled. He still remembers it to this day.

In spite of the IMSA rules changes, the Kremer Brothers entered their Porsche CK8. This was basically a 10-year-old 962 derivative with an open top, using a twin turbo 962 based engine. They went on to win the race outright as all the Ferrari’s broke down with valve issues, and the new Riley & Scott (Ford) struggled with teething issues.

Some say Porsche should have run, since the Kremer car won anyway. But Norbert Singer was quoted as saying “Porsche would not go racing with Hans Stuck, Mario Andretti, and Bob Wollek and drive around waiting for faster cars to drop out. We could only race at the front.”

Preparing the TWR-Porsche WSC for Le Mans

In March 1995, Porsche withdrew their entry for 1995 Le Mans for the WSC car, as the cars and parts were still sitting at TWR in Indiana. There were further negotiations between Porsche and TWR.

Norbert Singer visited TWR around March. After negotiations back and forth between the parties as to who owned what, the agreement was finalized. By the May/June 1995 timeframe, the agreed parts and cars were shipped to Weissach in Germany.

Starting in July of 1995, Porsche started work on the 911-GT1 car for 1996 LeMans. The two WSC cars were shuttled to a corner in the basement.

Reinhold Joest Acquires the TWR-Porsche WSC

By early 1996, Reinhold Joest, who had followed the TWR-Porsche project with some interest from afar, asked Porsche to let him have the WSC cars to run at Le Mans for the 1996 race.

Team owner Reinhold Joest, who in early 1996 asked Porsche to “loan” him the WSC cars to run at LeMans. Joest was convinced this car could do well at LeMans.

Norbert Singer and Porsche had done some calculations and determined that the WSC cars would have a better chance at overall victory (at Le Mans) than the GT1 cars in 1996. Porsche was interested in running the cars at Le Mans, thereby covering both “bases” of GT1 and WSC classes.

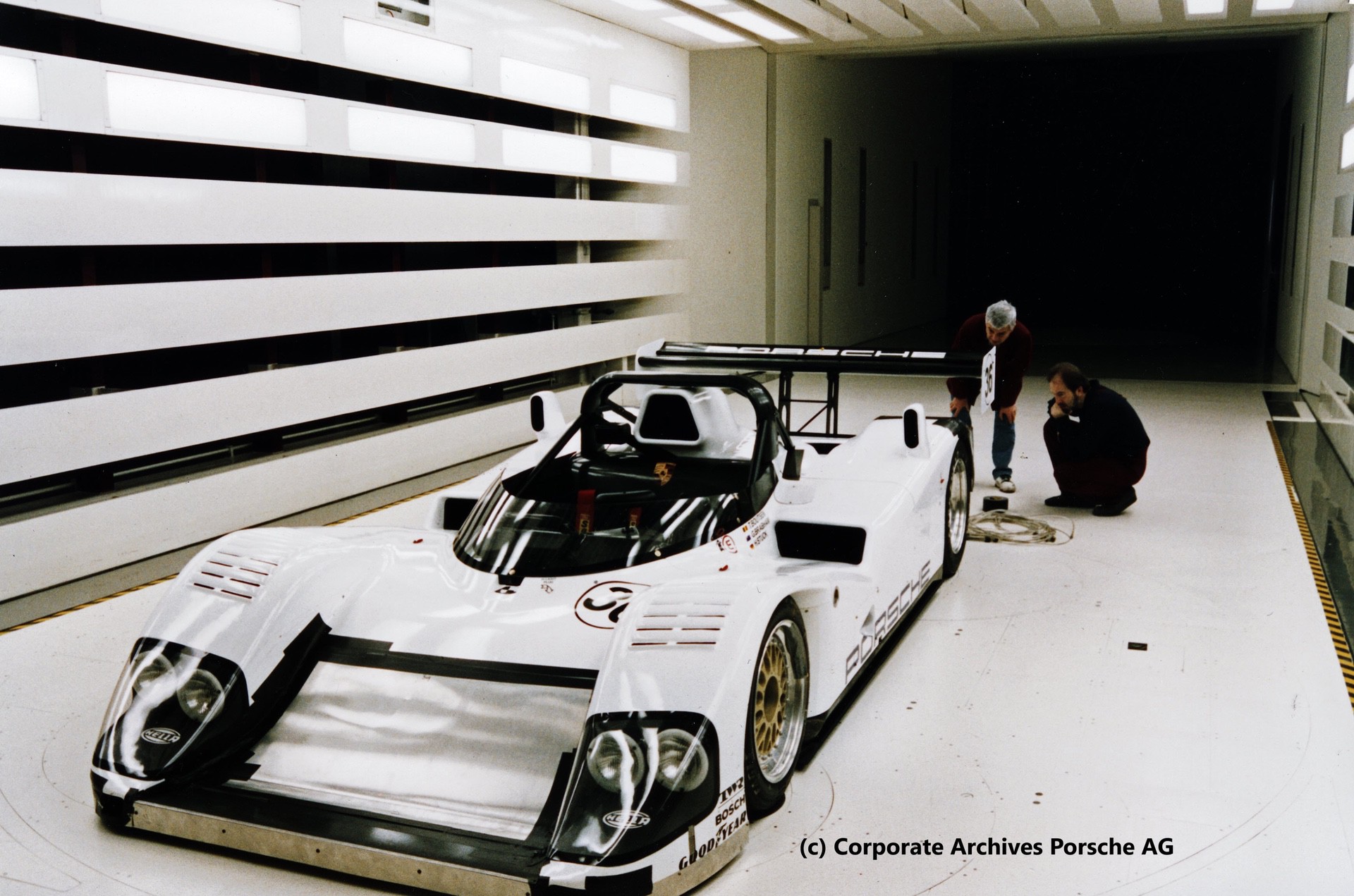

A small budget was put forth to develop the cars, since the Charlotte test in 1994 had shown that more work was still needed—specifically in aerodynamics. Aero work was completed at Porsche by February 1996 in the wind tunnel—and shortly thereafter, a successful test at the Paul Ricard circuit in the south of France.

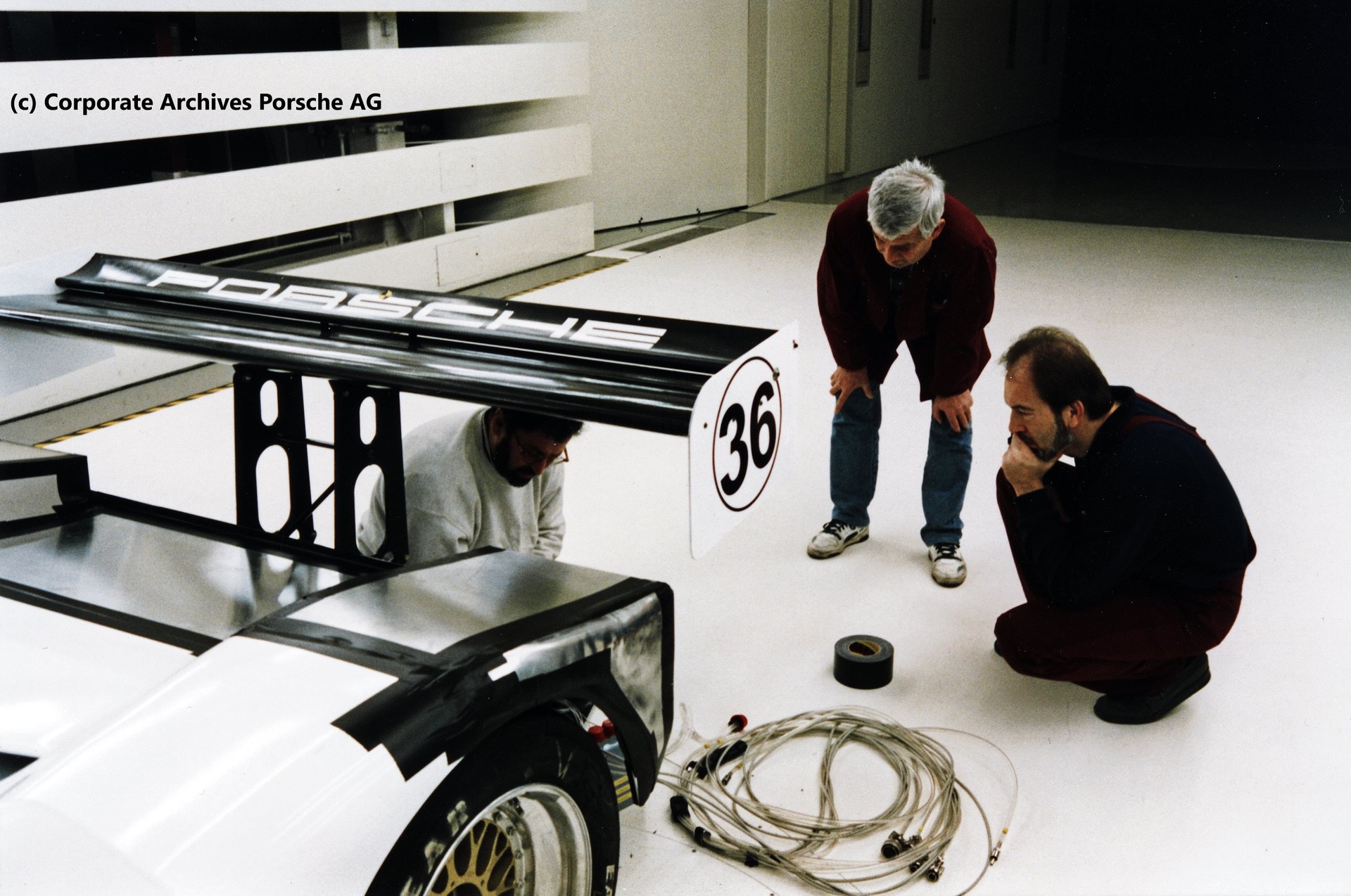

Norbert Singer maintained that wind tunnel work was needed. Here in early 1996, the car is getting evaluated at the Weissach wind tunnel. Already, new front bodywork is being tested.

A driver sits in the car to assist with air flow testing at the Weissach wind tunnel in early 1996.

New Rear bodywork also being assessed (note the difference from original Daytona setup). Bodywork for Le Mans was a little different from Daytona. This is also early 1996 at Weissach.

April 1996 pre qualifications at Le Mans indicated that Herr Singer’s calculations were correct, as the WSC car was over one second per lap quicker than the Porsche 911- GT1 car. The WSC car was running at 3:49.6 compared to the GT1 car at 3:50.9.

Le Mans tech inspection June 1996.

In June of race week—after initial setup struggles—Pierluigi Martini took the outright pole for the race in the WSC Porsche #8 (Martini, Theys, Alboreto) at 3:46.6, just ahead of the Courage of Jerome Pollicand at 3:46.79. Didier Theys, who by this time was driving the 333SP in IMSA, provided a lot of the setup ideas (based on the Ferrari) to improve the Porsche quite a bit during practice.

The fastest GT1 car was the Porsche, driven by Dalmas at 3:47.13. At the start of the race, the two WSC Porsches took the lead and ran in the top two for a good portion of the early goings. The #8 eventually faded with various issues, including a fuel leak, front nose change, and a sand trap excursion by Martini.

The car was eventually retired with 40 minutes to go, stopped on-course with mechanical issues. The #7 WSC of Reuter/Jones/ Wurz ran faultlessly and won the race outright over the Factory GT1 Porsche of Wollek/Stuck/Boutsen by one lap.

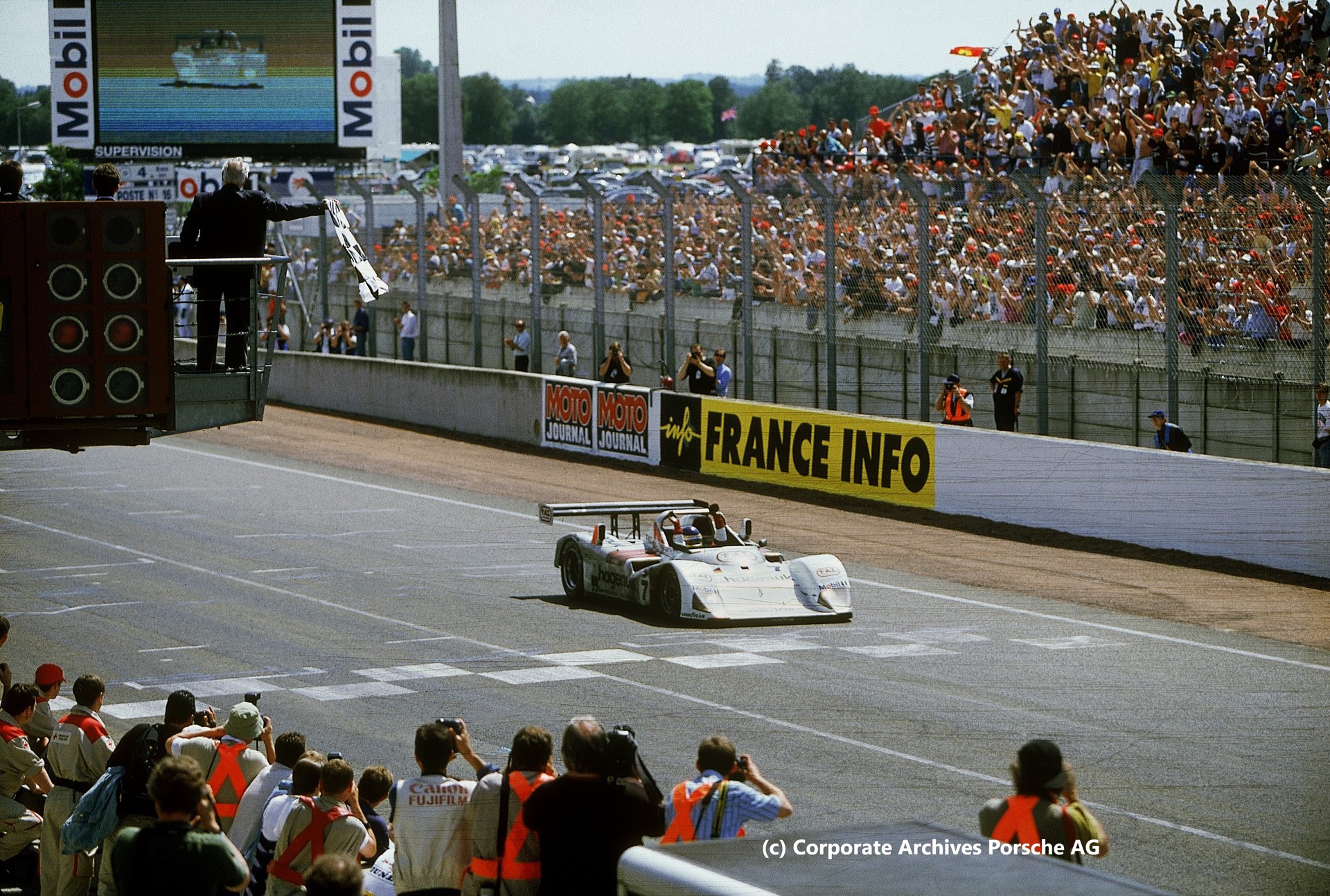

The outright winning car of Manuel Reuter, Davy Jones, and Alex Wurz. They beat the 911-GTI by one lap.

The second entry driven by Pierluigi Martini, Didier Theys and Michele Alboreto took the pole but succumbed to several issues during the race.

The WSC class ran with a smaller fuel tank than the GT1 class. However, the Joest cars managed to run only one lap less per stint with twenty liters less fuel in the tank. At times triple-stinting tires, they saved pit time over the heavier GT1 cars (by ACO rules fueling and tire changes could not be done at the same time during pit stops).

The race data reflects the ever so slight advantage of the WSC car. The #7 WSC had a total pit time of 50mins 56 seconds (over the 24- hour distance), while the Porsche GT1 car in second place spent 54 minutes 29 seconds in the pits. The gap reflects the one lap margin of victory. The car that had sat in the basement at Weissach was suddenly a Le Mans winner.

The winning car makes a night pit stop. The Joest crew saved pit time by frequently just refueling and triple-stinting tires.

Reinhold Joest had a deal from the factory to acquire the car for a “good price” if he won the race, and duly took the #7 car home. Both his car and the factory car sat idle for the rest of 1996.

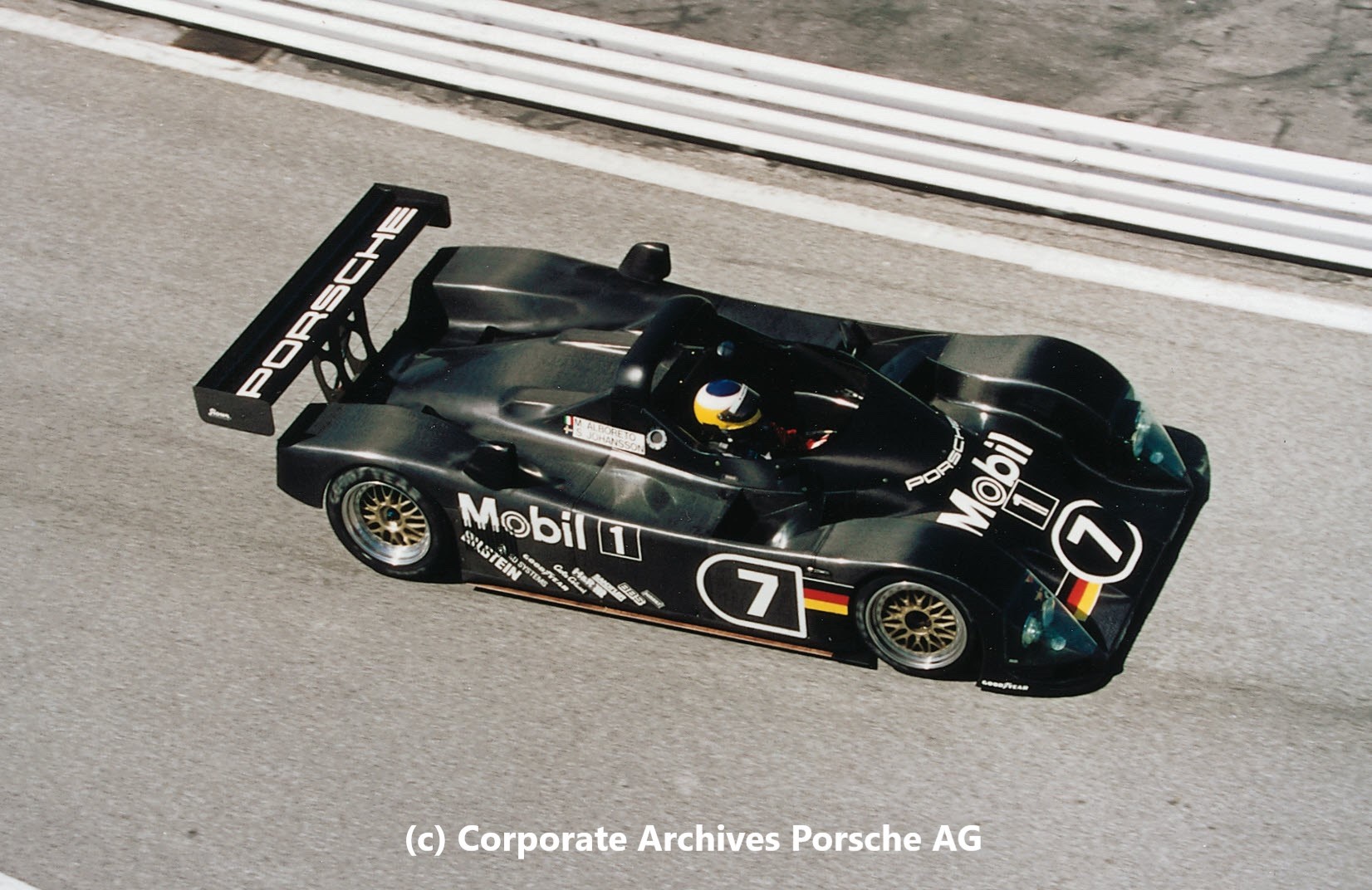

In 1997, Joest entered his single car again—while the factory focused heavily on the now further developed 911-GT1 cars. Drivers in the Joest car were Michele Alboreto, Stefan Johansson, and a new- comer, Tom Kristensen.

As the previous winner, the car was automatically qualified, and spent very little time running during the pre-qualification weekend. Alboreto did a 3:43.79 after limited laps and was second to Martin Brundle in the Nissan GT1 at 3:43.1.

In the 1997 LeMans, Reinhold Joest again entered with his car. Driven by Michele Alboreto, Stefan Johannson, and newcomer Tom Kristensen, it won again—beating the McLaren F1-GTR.

1997 Le Mans winner for the second year in a row—the TWR-Porsche WSC.

During the race week, Alboreto took the pole at 3:41.58, well ahead of the GT1 Factory Porsche of Boutsen at 3:43.3. The Joest car took the lead at the start and ran in the top three for the whole race with few issues.

With three-plus hours to go, the factory 911-GT1 Porsche was leading when an oil line broke, causing a retirement due to fire damage. The Joest WSC car then took the lead and ran un-challenged to the end, beating the McLaren F1 GTR of Raphanel, Gounon, and Olofsson by one lap. Again, both the cars sat idle for the rest of 1997.

The 1997 LeMans winner crosses the line again, beating the second place GT1 car by one lap.

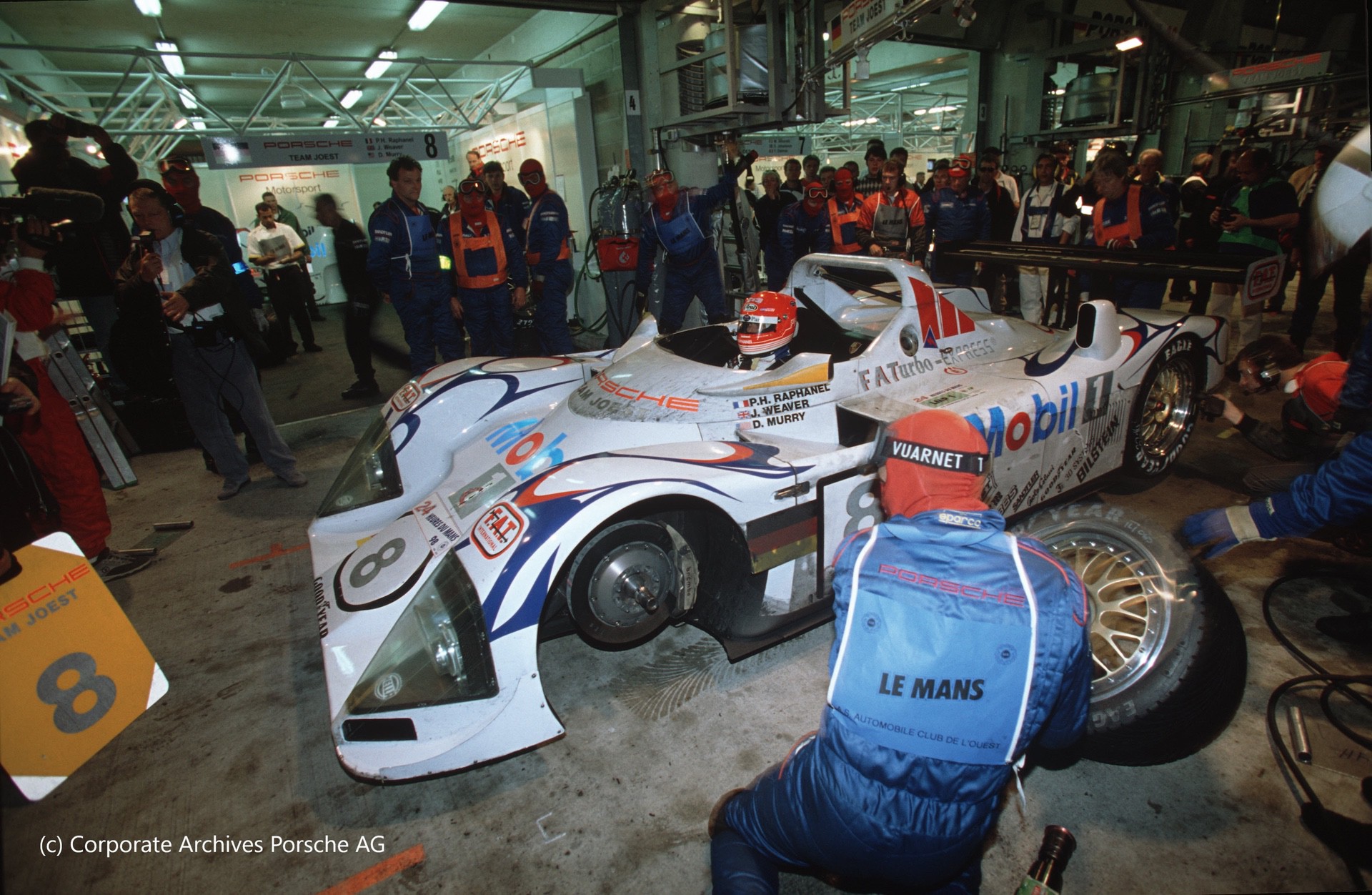

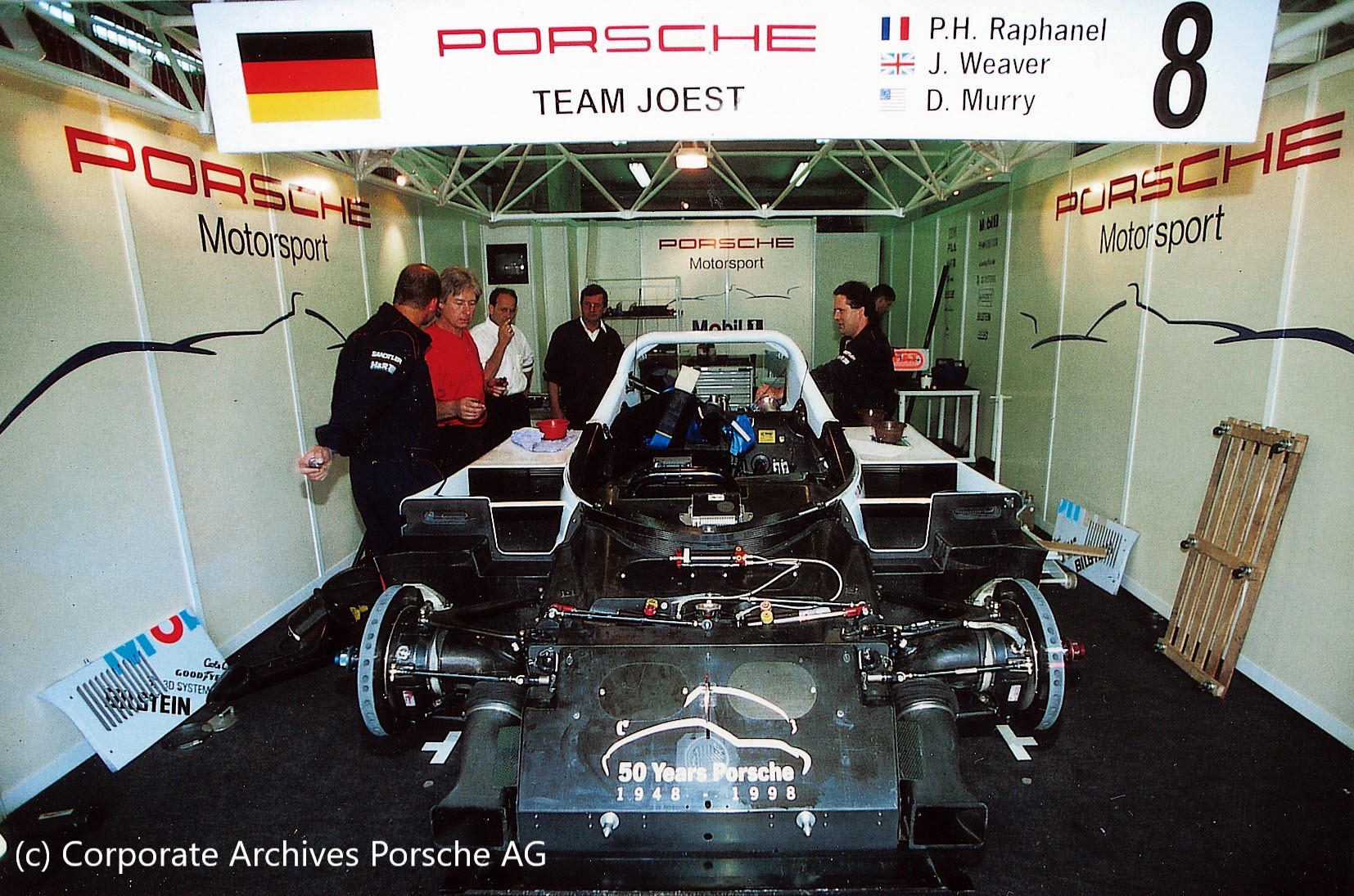

For Le Mans in 1998, two cars were again entered, this time under the Porsche factory banner with the designation of the cars changed to Porsche LMP1 98. Drivers in the Porsche LMP1 were James Weaver, David Murry, and Henri-Pierre Raphanel in one car, while Alboreto, Johansson and Yannick Dalmas drove the second.

By this time, the GT1 cars had been developed further and were quicker. BMW also entered two new V12 powered LMP cars (with now allowed 6.0-liter engines). Competition had caught up

The WSC cars were now 4-years old, and the ACO had changed the original IMSA WSC rules. They now allowed 6-liter engines, single roll hoops and diffusers. The LMP1-98 cars no longer had any advantage.

GT1 cars from Mercedes, Toyota and Porsche took the first five spots on the grid. The now designated LMP1-98 cars could only qualify 9th and 20th overall. Both cars were beset with problems and failed to finish.

The #7 of Alboreto and crew succumbed to electrical problems after only 5 hours. The #8 of the Weaver led crew retired after 14 hours when the rear body work parted company with the car at Arnage corner, breaking the wing mount in the process. The 911-GT1 cars of Porsche finished 1-2, finally in this year, having the advantage over the WSC (LMP cars).

In 1998, the two cars were entered and run under the Porsche Weissach banner. Alboreto Johannson and Dalmas drove this one but were out early.

The second car, driven by Weaver, Raphanel and Murry, also did not make the finish in 1998 due to a myriad of problems. By this time, the GT1 cars had caught up and rules had changed, giving the advantage to GT1 cars.

The #8 car sits in the garage at Le Mans in 1998. Numerous issues put the car out at the 14-hour mark.

The Porsche WSC car ran only one more race: the Petite Le Mans in 1998. Run over a 10-hour distance at the Road Atlanta Circuit in the USA, this race, as part of the ALMS (American Le Mans Series), would provide automatic entry to Le Mans 1999 with a victory at Atlanta.

Porsche again entered both the 911-GT1 car and the LMP-98. The GT1 car took the pole, and the LMP1-98 was third behind Gianpierro Moretti’s Ferrari 333SP. The GT1 Porsche flipped at high speed and was destroyed early in the race. The LMP1-98 Porsche (TWR-Porsche) finished 2nd to the Ferrari 333SP of Wayne Taylor.

Thus ended the career of the “Porsche-TWR.” Entering only four races, the car won Le Mans twice, had one DNF, and took second at the Petite LeMans in Atlanta. One car was retired to the Porsche Museum, and the other one still sits in Reinhold Joest’s private collection.

Chassis 002 currently sits in the Porsche Museum.

TWR-Porsche WSC-002 back in the basement at the Porsche museum circa 2019.

Cockpit chassis 002 at Porsche circa 2019.

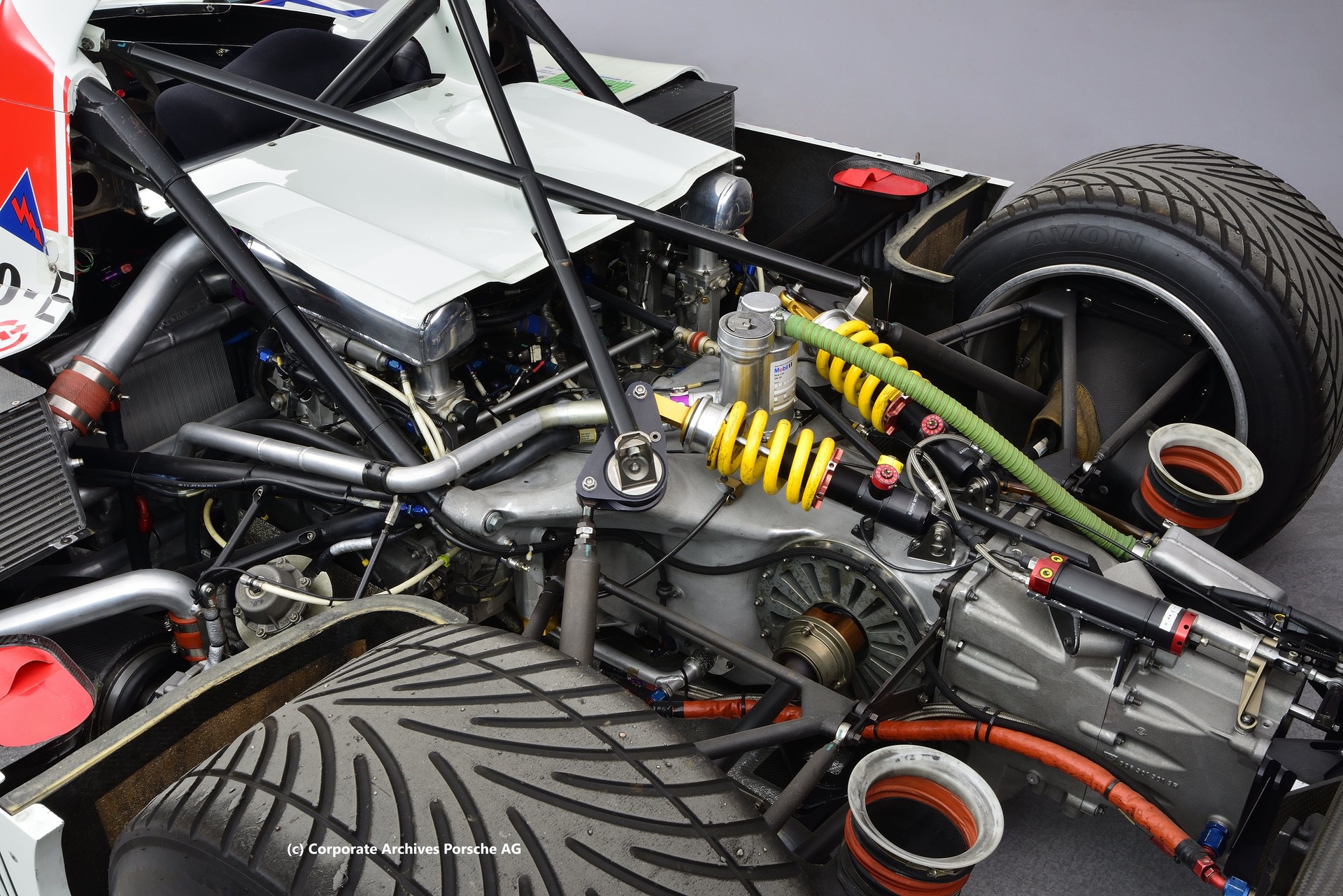

Chassis 002 Engine and gearbox at the museum in 2019.

The car from the basement—built from Jaguar and Porsche Parts—had been an unqualified (if unlikely) success!

I was a main player in this project and want to read your version. Thanks

0

Interesting and illuminating article, but, “1991 Le Mans…won by the Mazda 787B 4-rotor, due to a rules anomaly…” is just insulting. Mazdaspeed brought a legal car that covered more miles of Circuit de la Sarthe for a full 24 hours than any other. They won, period. Chassis and engine were largely in-house, unlike many cars in the article, most obviously the titular one. Ask Roger Penske how many championships he’s garnered by exploiting “rules anomalies.” For that matter, ask the TWR chassis designer; Rory Byrne might have some very interesting insights regarding his time at Benetton F1, for a start.

0