Definitive List of the Best Racing Cars Porsche Has Ever Raced

Porsche Race Cars

Porsche 917

Porsche 550 Spyder

Porsche 718

Porsche 904

Porsche 935/77

Porsche 935/78 ‘Moby Dick’

Porsche 911 RSR 2.14 Turbo

Porsche 911 GT3 R Hybrid 2.0

Porsche 919 Hybrid

Porsche 911 GT1 98

Porsche 936 Spyder

Porsche 956 C

Porsche 908

Porsche 959 Rally

Clearly this is Porsche month for us. First we wrote about all the wonderful 911s you can buy today, then we took on the best non-911 Porsche’s before tackling the hardest one, the greatest 911s in history. Now it is time for Porsche race cars and boy was this one tough. Lots of automakers like to brag about how their “racing heritage” informs their production vehicles, but nobody does it like Porsche. Their history in motorsports is unequaled and the machines they have made have won thousands of races over the years. Porsche has had success in Formula 1, Le Mans, Daytona, Nurburgring, GT Racing, Rally and much more.

Porsche started racing with lightweight versions the 356 but things really took off with the “giant killer” 550 Spyder. Dedicated race cars like the 550, 718, RS, and RSK models were the focus of Porsche’s race program through the mid-1960s.

Porsche first expanded its 8 cylinder flat engine to 2.2 liters in the 907, then developed the 908 with full three liters in 1968. Based on this 8 cylinder flat engine the 4.5 liter flat 12 917 was introduced in 1969. The Porsche 917 is considered one of the most iconic racing cars of all time and gave Porsche their first 24 Hours of Le Mans win. The 917 went on to destroy the competition in the cutthroat Can-Am racing series.

Porsche has had success with 911 racing variants since the beginning of that models history, winning the Monte Carlo rally. In the 1970s Porsche won the Targa Florio, Daytona and Sebring with the Porsche 911 Carrera RSR. The 911 also went on to win Le Mans in 1979 in the Porsche 935. Since then the 911 has campaigned both by Porsche and by privateers in thousands of motorsports series with great success. Even today, Porsche churns out specific racing models that enthusiastic buyers can snap up and drive in global races in addition to its formal race programs it competes in. Recent success in LMP1 with its Le Mans winning 919 Hybrid shows that Porsche can still mix it at the top.

In celebration of that history we pick the best racing cars Porsche has ever produced and tell you all about them. But first a primer on Porsche and racing.

A Primer – Porsche’s Start in Motorsports

Porsche has a long history and its illustrious racing and motorsport heritage is a big part of that story. You name the motorsports venue and series and there is a good chance Porsche has competed and and had success. 24 Hours of Le Mans, Rally racing, Formula 1, Indy, Carrera Cup (clearly) and much more.

It all started pretty early for Porsche. Because of his work with Lohner, Ferdinand Porsche was commissioned by Daimler to design a car that could be used to compete in the Prinz-Heinrich-Fahrt (the Prince Henry Trial.) While several designs were presented, Ferdinand’s model – the 22/80 PS – was selected to represent Austro-Daimler in the race. When the 22/80 PS finished in the top three spots of the Prinz-Heinrich endurance race event, the car was christened as the “Prince Henry”.

Then from 1925 to 1927 Porsche designed the 2-liter, 8-cylinder Mercedes Type S that won 21 of 27 races in the “Regenmeister.” The car was said to be almost unbeatable. This success led to Porsche being contracted to design a series of race cars (and the engines that powered them) that were to be driven in the Gran Prix of Germany. Known as “The Great Auto Union Project,” the development of the race car would keep the young Porsche engineering firm busy through most of the 1930’s.

In 1933, the governing body of the Grand Prix Circuit announced a new racing formula. Both Ferdinand and Ferry set to work on designs that would meet the new 750kg formula regulation. The early result of this effort was an experimental vehicle known as the P-Wagen project.

In 1946, Piero Dusio, an Italian soccer player, businessman and racing driver, approached the firm to design a new Grand Prix race car. Ferry recognized that this might be the opportunity he’d been seeking to free his father from prison. Dusio gave the Porsche firm just 16 months to complete the car. Dubbed the Porsche Type 360 Cisitalia, the Grand Prix racer featured a supercharged, mid-mounted, 1.5 liter flat-12 cylinder engine that produced 385bhp at 10,500rpm. It was paired to a complex four-wheel drive transmission assembly. It never advanced beyond the testing phase, due mostly to the limited timeframe in which the car was to be completed so that it could compete in the Grand Prix circuit. Despite this, the car was also the first ever to bear the “Porsche” name.

The rest as they say is history. Now, onto the cars.

Best Porsche Racing Cars

Porsche 917

Few cars, of any make, can match the legendary Porsche 917. Developed in a time of motorsports turmoil, as regulations were being changed to reduce top speeds of race cars, it emerged as one of the fastest, most reliable, and winningest Porsches ever.

The 917 emerged from the regulation change implemented by the CSI, the at-the-time separate sporting arm of the FIA, in 1968, which limited prototype cars (Group 6) to 3.0L engines, and sports cars (Group 4) to 5.0L engines, with a requirement of 50 road-going homologation versions. Before these changes, Porsche had a very successful sports car race history, with the 904 Carrera GTS, the 906 Sports Car, and the 907 Sports Car winning in their classes. However, Piech wanted more than just class wins, he wanted the overall win at races, and the fact of the matter was that the Porsches could not keep up with the Ford GT40 and Ferrari P-series prototypes.

When the regulations took effect in 1968, Stuttgart offered forward the 908, a 3.0L flat-eight prototype, while behind the scenes, work on the 917 had already begun. Because many manufacturers balked at having to invest in 50 homologation specials to produce their Group 4 cars, the CSI reduced that number to 25, and Piech pounced. He saw his chance to get an outright win as the 7.0L Ford GT40 had to cut power and engine size, and the Ferrari P-series were retired from competition.

Introduced in 1969 at the Geneva Motor Show, the Porsche 917 had a 4.5L flat-twelve engine, stellar looks, and caught the attention of both customer racing teams and the CSI alike. To allow the car to race, the CSI wanted to see the 25 homologation models, and set the inspection date for barely over a month later. This led to one of the most famous efforts at Stuttgart, the “secretary car,” as everyone from every department, including the secretaries, were drafted in to build 917s.

When the CSI arrived, there were 25 917s lined up outside of the factory, although only 5 actually ran, and the rest had tractor engines in them, with bodies draped over the frame, to give the appearance of being completed. Piech offered the CSI inspectors the opportunity to drive any of the 25 units, but that offer was declined, as Piech had surmised it would be, since the CSI wanted more manufacturers in the Group 4 class.

Eventually, those 25 cars would be completed, and the 917 started racing in 1969… and failed horribly. It was discovered that the 917 was incredibly unstable at high speed, and while it had been homologated in time for Le Mans, factory drivers and customer teams alike preferred to race the 908 Spyder, which finished 1st through 5th at the 1969 1,000 KM of Nurburgring, while the sole 917 entered finished in 8th place.

Three 917s were entered in the 1969 24 Hours of Le Mans, two from the factory and a factory model loaned to John Woolfe Racing. One of the 917s set the fastest speed in practice down the Mulsanne Straight, as well as set the fastest lap, so word began to percolate that Porsche might have a challenger. Unfortunately, John Woolfe suffered a fatal crash in the 917 on the first lap, as he had not done up his seat belts properly after the traditional Le Mans sprint-across-the-track start. Further compounding things, both factory 917s dropped out after 300 laps with identical clutch bell housing failures.

Things changed for 1970, however, as Piech had ordered the 917 back to the drawing board to rectify the stability issues, which created the now legendary 917 Kurzheck (Short tail), better known as the 917K, which was astonishingly stable at any speed. Simultaneously, a 917 Langheck (Long tail), or 917LH, was created to achieve top speed down the Mulsanne Straight. The development worked, and in 1970, driven by Hans Herrmann and Richard Attwood, a 917K crossed the line first overall, giving Porsche their first win at Le Mans.

After Porsche had won Le Mans twice back to back, development began on more models of the 917, including a turbocharged version of the 917’s flat-twelve for CAN-AM, and a flat-sixteen prototype. That CAN-AM model eventually became the 917/10, developed in collaboration with Mark Donahue, a legendary race car engineer, and Penske Motorsport, which eventually was capable of handling up to 18 to 20 PSI from the turbo, which put down over 800 HP to the rear wheels.

In the hands of Penske Motorsport, the Porsche+Audi liveried car, driven by Mark Donahue and then George Follmer, would go on to win the 1972 CAN-AM championship outright, as no other car on the grid could keep up. It was often cited as one of the ugliest, loudest, meanest, wildest race car on the grid, but it got the job done.

For 1973, a 5.4L version of the CAN-AM engine was created by Valentin Shaffer, which was placed into the 917/30, producing a nigh unbelievable 1,100 HP when the turbos were turned up to full. In race trim, it ran at 900 HP, and in the hands of Mark Donahue, absolutely decimated the 1973 CAN-AM championship, practically winning every race.

That same car also set a lap speed record of 222 MPH (356 KPH) around the Talladega Oval in Alabama during a race, and to this day, that still stands as one of the fastest race laps ever run, by any car on any circuit.

The 917 program, which ran for most of the 1970s, was one of the most vitally important periods for Porsche Motorsport. From this era, the dangerously fast 956 was born, the legendary 935 911 program was greenlit, and the 917, in K, L, /10, and /30 trims, was the dominant race car in the world, bar none. Without the 917… Porsche’s racing history would have been a lot different.

Porsche 550 Spyder

Before 1953, Porsche cars had been used for racing, but none of them had been outright designed from the very start to be a racer. That was changed when the 550 Spyder came about, which would become the car that cemented Stuttgart as a center for racing performance and excellence.

The 550 Spyder was one of the few Porsche cars that was designed from the outset to be mid-engined, which was seated in a lightweight tubular steel flat frame. Overtop, lightweight steel and sometimes aluminum was hand shaped into a monocoque body. Adding just enough controls to drive the car and provide driver information, it was a sparse, spartan car, but with the simplifications, it weighed just 1,212 lbs, or 550 kg, with a 1.5L flat-four engine producing anywhere from 110 to 135 HP.

This made it ridiculously fast for the time, and it won the very first race it entered, at the Nurburgring in 1953. All said, of the original specification, 90 units were sold. Due to how the car was manufactured, it was also deemed as road legal in many countries around the world, and seeing a 550 Spyder drive to the race track, take part in a race, and then drive away was not uncommon.

Updated a few years later with a steel space frame and more grunt from the engine, the 550A Spyder was a pure race car. It made its racing debut at the 1956 1000 KM of Nurburgring, but its most famous success was in Italy. During the 1956 edition of the legendary Targa Florio, one of the toughest road races of all time, Umberto Maglioli was the first to cross the finish line in a 550A RS Spyder. To do this, he had to outpace Ferrari’s, Maserati’s, Alfa Romeo’s, and the like, all of which were extremely competitive. It was the first of 11 Porsche victories before the Targa Florio ended in the late 1960s.

Porsche 718

The namesake of the current Boxster and Cayman models, the Porsche 718 was the direct successor to the 550A RS Spyder. Named the 718 RSK, it debuted in 1957 and was soon winning around the world. The RSK after the model number breaks down into “RennSport” (RS), and the K designated a new front torsion bar springs that formed the shape of a K if you laid it down on its spine, with the two arms pointing upwards.

The 718 soon became known as the “Giant Killer,” as while Ferrari’s and Aston Martin’s of the time were weight down with big V12 engines and long hoods with small cabins, the mid-engined Porsche was lighter, nimbler, and due to the steel space frame and suspension setup, extremely rigid. This made it nearly telepathic in response to driver inputs, and it soon became the top tier Porsche racer, taking part in everything from Le Mans to the 12 Hours of Sebring.

There were a number of regional differences for the different race series it entered, such as the RS60 with 160 HP and meant to race (and won) at Sebring and the Targa Florio. The RS61 was an evolution of that car, while the wild W-RS upped the engine to 2.0 liters, upped the cylinder count to a flat-eight, and upped the power to 240 HP, with the car still weighing in at a sparse 640 kg, or 1,411 lbs. While it managed only 8th at Le Mans, it participated in Formula One as Porsche’s entry for a full season before they switched to focus on the 904, and it dominated many European Hill Climb contests. Despite only 3 being made of the W-RS, it is still considered the ultimate evolution of the 718.

More: Porsche 718

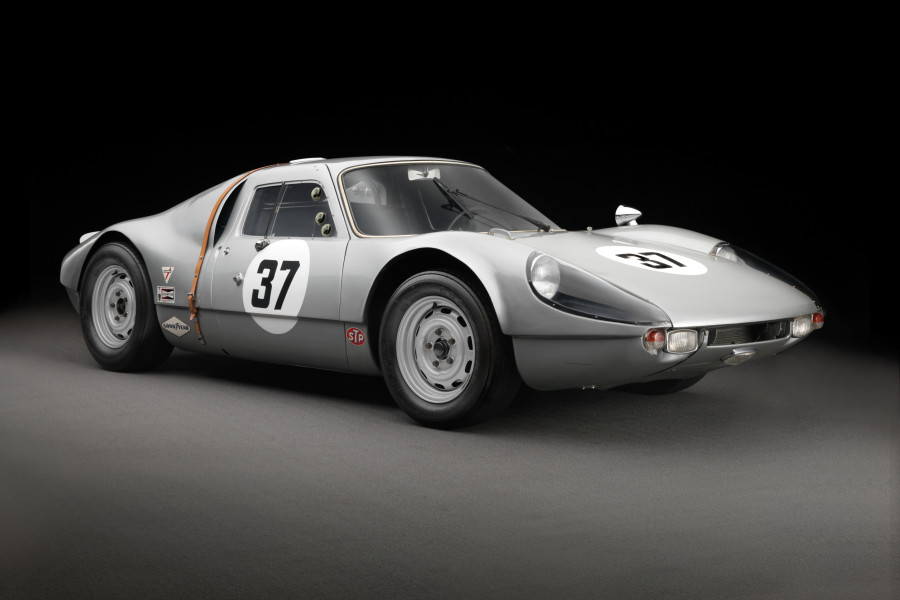

Porsche 904

In 1962, Porsche withdrew from Formula One at the end of the season, deciding instead to focus on sports car racing. This was because of a new set of regulations regarding GT cars for endurance and sprint races announced by the FIA, and the 904 was the car that was designed and built to meet all of them.

Expertise that was gained while developing and then racing both the 550 and 718 RSK race cars were instrumental in the design of the 904, which was meant first as a road-going car because of the homologation regulations needing 100 production cars. However, while those 100 cars were fitted out with comfortable interiors, heaters, and the like, the chassis had been designed to hold any of a variety of engines, depending on what series the car would race in.

The original, dedicated engine for the car was going to be shared over from the Porsche 901, a flat-six unit that is extremely familiar to many enthusiasts, as the 901, after some trademark issues, was renamed to the 911. Eventually, the 587/2 flat-four from the last years of the 356B was used, as it married well with the balance of the car and its light weight, while giving enough performance, 180 HP, to be competitive.

Of the 120 units produced, a large percentage were sold to customers or customer racing teams, meaning that other engine options were developed as the car’s popularity grew. It was winning hill climb events, road rallies, and the like, so Porsche developed 2.0L flat-eight known as the Type 771 which produced 210 HP.

A flat-six eventually made it into the car, although all six of the 904/6 cars were Porsche works race cars. It was the unit from the 911 that came across, bringing with it 200 HP and all of the development expertise that had created it in the first place. This made the 904/6 extremely reliable, something that is a bit of a hallmark of almost every Porsche racing car since.

The 904 won a large portion of races it was entered into, including an outright win at the 1963 Targa Florio, and it absolutely dominated the 2.0L class in 1964, pretty much taking the sports car championship it was designed for in a clean sweep. In 1965, the 904 again was the class of the field, but other manufacturers had started to develop cars that could compete with it. The 904 ended production in 1965, with its replacements, the 907 and 908, taking up its torch.

More: Porsche 904

Porsche 935/77

If there was ever a car that could be described as “the Porsche,” it was the 935. A very popular choice in Group 5, GTP, and GTX classes, depending on which series they raced in, variants of the base 935/76 would go on to win almost a decade’s worth of races. Two variants, however, rose to become legendary, the first of which is the 1977 935/77.

The 935/77 was originally offered to customer teams as a variant of the factory works, Martini-sponsored version of the 935, which were technically superior. These customer 935’s were based on the 1976 Carrera RSR 2.1 Turbo, which itself was a variant of the original 1974 RSR, but benefitted from the technical advancements and sheer research and development thrown at that prototype car.

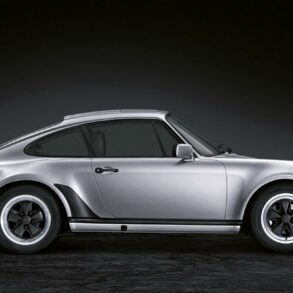

Using the base framework of a Type 930 Porsche 911, Norbert Singer, head of design and engineering at Porsche Motorsports in the 1970s and someone that read those rules and regs very carefully to find any advantage, was able to drastically alter the bodywork of the base car. Huge fender flares were made, along with a gigantic wing (although not the biggest on a 911-based race car), which gave the car a squat, powerful stance. A very clever and legal interpretation of the rules allowed for the headlights of the car to be placed in the front bumper, allowing for the development of a flachbau (flatnose) front end, which was very low and quite long for the best aerodynamics.

The 930 unitary steel monocoque was retained, although it was reinforced by the aluminum roll cage that was both within regulations but built intelligently to add stiffness to the car. The body itself was made of resin impregnated fiberglass, which was stiff enough to handle the aerodynamic pressures of racing, but also extremely light. Remember, this car was made before carbon fiber was fully researched and developed for racing.

15 inch wheels held wide, sticky tires both front and back, under just about 5 inches of extra width to the car’s track in both front and rear. Plexiglass windows and getting rid of any part that was not absolutely required for the car to race meant that when finished, at full wet weight but without a driver, the car was literally 90 kg (~200 lbs) under the regulations minimum, and had to have performance ballast added to bring it up to spec.

The engine of the 935/77 was the best part of Singers’ interpretation of the rules, as there was a 1.4:1 equivalency ratio for naturally aspirated against forced induction engines. The 2.9L turbo flat six was right on the limit of the equivalency ratio to a 4.0L naturally aspirated engine, but it was the comically large turbo that brought the power. In a housing that was about the size of a human head, the KKK turbocharger could provide boost anywhere from 19.5 PSI (1.35 bar) to 22.5 PSI (1.55 bar). In power terms, when everything was turned up to maximum, that little 2.9L engine was laying down over 650 HP at the flywheel, and close to 600 HP at the rear wheels.

The engine was also quite advanced, even by today’s standards. Dual ignition, spray-bar type lubrication from a dry sump system, a 908-derived fuel pump for reliability, and a direct-boost control system operated by, of all things, a cable attached to the turbo intake. This meant that the driver could adjust the boost on the fly, something that was a radical new idea at the time. For reliability, however, the boost was often left in the middle, so the engine would be producing close to 600 HP, or about 550 to 560 HP at the rear wheels. Some customer teams, however, turned the wick up on theirs to have 630 HP at the flywheel, but to keep performance fair, they had to carry 55 kg (122 lbs) of extra ballast to compensate.

All said, this monster of a race car was able to lay down 650 HP in a chassis and body that combined, before ballast, weighed just 900 kg wet (1,984 lbs). As the minimum weight required was 970 kg (2,138 lbs), this meant that at every race, the 935/77 was carrying ballast, and when that gigantic KKK turbo spun up, it often didn’t matter. Nothing in 1977 could catch the car down a long straight as it simply catapulted itself towards the next corner. The funny thing is, though, that this is not the most extreme variant of the 935, oh no. That came in 1978, as we are about to explain…

More: Porsche 935

Porsche 935/78 ‘Moby Dick’

The most iconic 911-based race car to ever turn a wheel in anger? Almost any Porsche enthusiast would agree that the 1978 935/78 was the car. Not just a great Porsche, but the car that defined Stuttgart’s utter dedication to racing and winning.

Racing under the FIA’s Group 5 “silhouette series” regulations, where the race car had to mostly resemble the road car it was based on, Norbert Singer took great liberties with the design, to the point that he was literally at the margins set out in the rules, if not half a millimeter over. Everything about the 935/78 was turned up to 11, making it both an instant classic and an iconic race car.

The car, like the 935/77, used the unitary steel monocoque of the Type 930 911, but unlike the /77, the front and rear subframes were replaced with aluminum. Both the front and rear body was lengthened, giving the car a much shallower nose to cut through the air better, and a tail that stuck out so far that it resembled a whale. This was where the term “Whale-tail” was derived from for the spoilers that started to show up on 911s in the 1980s, as well as the car being nicknamed “Moby Dick.”

The car was absolutely slammed to the limit, lowering the car a juicy 75 mm from the base 930. The entire floor was replaced, creating a smooth undercarriage that naturally created ground effect aerodynamics. The tail, which extended almost 2 feet beyond where the rear of the engine was visible through the chassis, was hollow and shaped to create a massive venturi effect, in effect sucking the car hard to the road. That was aided by a massive wing on top of the whale tail, that was there more for high speed stability than pure downforce.

The engine, a 3.2L flat-six, had to use production car internals in the block, but the cylinder heads were free to modify, again something discovered by Norbert Singer reading the regulations very carefully. Thus, the 935/78 had the first implementation of water cooled cylinder heads in a Porsche race car, as well as having dual overhead cams per bank (four total cams) and four valves per cylinder. Of course, being a 935, this engine was paired with a KKK turbocharger that was bigger than the one on the 935/77.

When dialed up to qualifying spec, the turbo produced nigh on 25 PSI (1.7 bar) of boost, with over 850 HP at the flywheel possible. When run in race trim at 21.8 PSI (1.5 bar), it still was throwing down 750 HP at the flywheel, and just about 680 to 700 HP at the wheels. The radiators to cool this monster were mounted in the side vents of the massive rear wheel wells, a design inspiration that would make it to pretty much every 911 Turbo since the 1970s, while underbody airflow was used to cool the block and transmission.

The car first appeared at the 6 Hours of Silverstone, where it won outright while coming close to setting the largest margin between the winner and second place at the race. As it was designed to race at Le Mans, the car was not used again until the sports car championship returned to Le Circuit de la Sarthe that year. In the hands of Rolf Stommelen and Manfred Schurti, the 935/78 set a new top speed record for a silhouette race car of 227 MPH (366 KPH) down the Mulsanne Straight, a speed that no other factory works 911 based race car has been able to achieve since.

Despite the incredible speed, the car suffered from engine problems and spent time in the pits, eventually coming home eighth overall. Yet, it had beaten every other car in the silhouette prototype class in top speed, and firmly etched itself into the history books. The works 935/78 was raced only two more times before being permanently retired and placed in the Porsche Museum, where it still sits today.

A few customer teams made “replica” 935/78s from blueprints of the works car, but the actual Moby Dick itself, despite the enormous cost to design and develop, took part in only four events. Yet, those four events were enough to make this car a legend.

More: Porsche 935/78 ‘Moby Dick’

Porsche 911 RSR 2.14 Turbo

The 1974 Porsche 911 RSR 2.14 Turbo is a car that not only inspired a full decade of racing cars after it, but also was one of the milestone cars in Porsche’s entire history. It was a car of firsts, and despite its extreme rarity, it was also a research and development lab on wheels that would set the standard for the next 20 years of 911 road cars.

Until 1974, Porsche had been showing the world through excellent cars like the 550 Spyder and the 718 RSK that a lightweight car with a small engine could, quite literally, run laps around big, heavy, large engined GT cars. It was actually during the development of the 917, especially the 917/10 and 917/30 for CAN-AM, that the inspired decision was made to show the world what small displacement forced induction engines could do.

To showcase turbocharging, in hopes to create interest for the newly announced 1975 911 Turbo road car, the RSR was created to fit tightly within the FIA’s Group 5 regulations, especially the requirement for the engine to be at 3.0L or less in displacement. While they could have gone mad and made a twin-turbo 3.0L flat-six, in the interests of keeping the 911’s near perfect balance and dynamics, a 2.14L flat-six was developed instead. It did get two turbos, however, both of them some of the largest, at the time, turbines that KKK had ever made.

The engine was also a technical powerhouse. The crankcase was made of magnesium, the connecting rods were made of ultra-strong but ultra-light forged titanium, two large-capacity oil pumps for redundancy, mechanical direct fuel injection developed by Porsche and Bosch, a dual ignition system, and even had sodium-cooled intake valves, which was seriously space-aged technology in the 1970s. The engine, with all the tech and design, ended up being able to produce an astounding 500 HP and 405 lbs-ft of torque.

That engine was then mounted into a steel tubular space frame chassis, and the car was draped in fiberglass body panels, engineered to be at the minimum spec needed to save as much weight as possible. Those body panels were also shaped to create as much aerodynamic downforce as possible, including the rear deck lid that would become the inspiration for the 935/78’s “whale tail” spoiler. All said and done, the car weighed a scant 825 kg, or 1,819 lbs.

During testing for the 1974 24 Hours of Le Mans, even Porsche were stunned when the tiny car with the tiny but giant heart lapped the course a full 11 seconds faster than the RSR 3.0 from the previous years. A combination of the incredibly mid-range torque and the top-end power meant that the car was seriously threatening the 200 MPH threshold down the Mulsanne Straight, a feat that a Porsche just a few years later would smash through.

Four total 911 Carrera RSR 2.14’s were made, with all four turning their first laps in competition at the 1974 1,000 KM of Monza. Dubbed R5, R9, R12, and R13, they were all title sponsored by Martini, using the classic livery that just works on a Porsche. Due to their massive technical innovations, however, the cars had to race in the Group 5 Prototype class, alongside dedicated prototype cars like the Matra-Simca MS670C and the Gulf Mirage GR7. Despite racing cars that were massively above its class, the RSR 2.14s were able to achieve second place finishes at both the 6 Hours of Watkins Glen and the big race, the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

As a result, not only did Porsche sell a lot of 911 Turbos in 1975, for every generation since the Turbo model has been the flagship. Yes, there are 911s in every section of the sports car market, but it’s the Turbo, ever since Porsche proved what you can do with six cylinders, a small displacement engine, and two stonkingly huge turbines, that has led the charge in every Type since the 1980s.

More: Porsche RSR Models, 1974 Porsche 911 Carrera Turbo 2.14

Porsche 911 GT3 R Hybrid 2.0

The 2011 Type 997 911 GT3 R Hybrid 2.0, apart from being one of those mouthfuls of a model name, was meant to be, and was, a precursor of just what racing would become. Porsche partnered up with Williams Advanced Engineering, aka Williams F1, to develop a performance hybrid system that was based on the Formula One Kinetic Energy Recovery System (KERS), but using a flywheel to store energy instead of a battery.

Two electric motors, one for each front wheel, were mounted in the front of the car, with a flywheel energy retention system mounted where the passenger seat would be in a road-going 911. That flywheel, which needed to be at 28,000 RPM just to be able to start storing energy, could reach a maximum of 37,000 RPM, and deliver that energy instantly to the electric motors, giving the front wheels approximately 218 HP.

Combined with the already powerful 4.0L flat-six in the rear generating 470 HP, the car had a maximum power output of 688 HP, often running closer to a nominal 670 HP, with torque out of the stratosphere due to electric motors generating 100% of their torque at 0 RPM. While the original GT3 R Hybrid was a game changer, we had to pick the GT3 R Hybrid 2.0 for this list as it didn’t change the game as much as pick up the board, throw it out the nearest window, and create an all new game from scratch.

It was also massively advanced in materials as well as its powertrain. The windows were a new formulation of polycarbonate that is now the de facto standard on all Porsche race cars. The body panels used a new weave and type of carbon fiber. Each wheel was suspended by on-the-fly electronically adjustable suspension with dual coil springs and a Sachs gas-pressure fixed-position damper. The steering rack was power assisted by both hydraulic and electric systems.

The car, with all of the tech on board, weighed just 2,866 lbs (1,300 kg), and when running with a fully spun up flywheel and maximum power, would absolutely decimate 60 MPH in under 2.5 seconds. For comparison, that is a good benchmark for full electric hypercars today in 2023, and a 911 GT3 R was doing that in 2011.

Although it had a governed top speed of 175 MPH, when the car was raced during an exhibition event for the American Le Mans Series at Laguna Seca in 2011, it was the class of the field. Not only did it start last, it completely monstered the entire GT field within the first 10 laps, and then left the rest of the GT cars far, far behind in its rearview mirrors.

Because Porsche had proven that a hybrid race car could work, and because of the FIA and ACO developing new rules and regulations for prototype racing for the 2010s, it is not outside of reason to state that the 2011 Porsche 911 GT3 R Hybrid 2.0 was the inspiration for the next car on our list, which took the hybrid idea and ran with it.

Porsche 919 Hybrid

In racing, the term “domination” is rarely used, as to utter the d-word means accepting the fact that one team, one driver, one car, or any combination of those three showed up and no one else had a chance. Yet, the word domination is carried by the Porsche 919 LMP1 Hybrid, one of the greatest race cars ever made.

Stuttgart had not hoisted an overall Le Mans victory trophy since 1998, with the 911 GT1. After pulling out of the very expensive top level Le Mans Prototype 1 (LMP1) class, they focused more on GT racing, with the 911 race cars, with a brief foray into LMP2 racing with the RS Spyder. While there were many class wins, and a couple overall wins during the years between 1998 and 2014, when the first 919 LMP1 Hybrid debuted, none of those overall wins came at the prestigious 24 Hours of Le Mans.

When the 2014 iteration debuted, it was one of the, if not the, most advanced LMP1 car on any grid. It used a 2.0L V4 engine with a turbo designed by Porsche and Garrett, combined with a front-axle based hybrid-electric motor, with energy being stored in a battery pack that took up the right half of the cockpit. The engine produced 500 HP all on its own, making it one of the highest specific output V4 engines ever made. Add on top of that the Porsche-designed hybrid motor that provided another 402 HP, and the car, which weighed 875 kg (1,929 lbs), is one of the few cars outside of Formula One that has a power-to-weight ratio greater than 1:1.

The 919 LMP1 Hybrid made its debut at the 2104 6 Hours of Silverstone, where it finished third behind the two Toyota LMP1 Hybrids. This started a (friendly) rivalry between the two teams, but it was at Le Mans that Porsche realized that they needed to become a bit more ruthless. The top 919 came in 11th overall, and that, quite simply, was not good enough for Stuttgart.

The d-word started in 2015, when a totally revamped, reworked, and updated 919 debuted, claimed by Porsche to be “90% different and better.” It immediately claimed pole position at the endurance races at Silverstone and Spa, and for the first time since 1998, achieved pole position at Le Mans. The 2015 919 LMP1 Hybrid monstered the field at Le Mans, and Porsche, just one year after placing 11th, took the overall win and second place, with their third car coming in 5th. The 919 did not lose a single race after Le Mans, handily winning the 2015 WEC Championship.

After that win, the 2016 and 2017 variants of the 919 LMP1 Hybrid were simply unmatched in technology, power, and victory, dominating over the technical powerhouses that were Audi Team Joest and Toyota Motorsports, their main LMP1 rivals. The 2016 and 2017 Le Mans races were won overall by Porsche, they came second in the 2016 WEC Championship, and won it again overall in 2017.

Due to the rising cost, literally into the hundreds of millions of dollars, to continue racing in LMP1, Porsche retired from the class after 2017, and created one more version of the 919, the incredible 919 Evo. A car that was not bound by any rules of regulations, it was a technical showcase of what the 919 was truly capable of. This was showcased in June of 2018, when the 919 Evo lapped the Nurburgring Nordschleife, a 12.94 mile (20.8 km) circuit, in an Earth-shattering 5 minutes 19.546 seconds, a record that it holds to this day as the outright and overall lap record at the track.

To give you an idea of just how fast and powerful that lap was, with the systems not bound by any rules, the 919 Evo put down 1,144 HP and achieved a top speed of 230 MPH (370 KPH), with its average speed at 145.6 MPH (234.3 KPH). Quite simply, no other car has even come close to that average speed.

The Porsche 919 LMP1 Hybrid was simply dominant, in everything it did. Full stop.

More: Porsche 919 Hybrid

Porsche 911 GT1 98

Any Porsche enthusiast worth their salt was waiting for this car to show up on this list, so here it is!

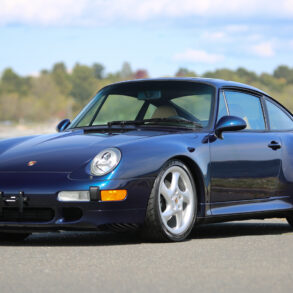

The 1998 Porsche 911 GT1-98 was the culmination of over three years of research, development, and evolution, the final (and best) version of the 911 GT1 project. Starting with a Type 993 911 GT2 that was upgraded to race car status, the project was initially a failure as the car was nowhere near the level of the Ferrari F40 LM’s and McLaren F1 GTR’s that were dominating the GT1 class.

After the 1996 911 GT1 and the 1997 911 GT1 Evo, Porsche brought the completely new, totally redesigned 1998 911 GT1-98 to fight against the Mercedes-AMG CLK GTR and the Toyota GT-ONE, both extremely powerful and fast cars. The GT1-98 had a much more prototype-style body compared to the previous two iterations, and was made entirely of carbon-fiber, the first time a Porsche race car’s entire chassis and monocoque was one continuous carbon fiber structure.

The GT1-98 carried a heavily modified Type 993 911 flat-six, at 3.2L with two KKK turbos, to produce 592 HP. That engine was mated to a 6-speed sequential transaxle. The car weighed only 950 KG (2,094 lbs), so it was anything but slow, especially with its new, slippery body, but it struggled throughout the 1998 International GT Championship to match pace with the Mercedes. This was mostly blamed on the air-restrictor rules in place at the time for turbo engines, which starved the top end power of the twin-turbo, allowing the naturally aspirated V8 of the CLK-GTR to simply haul it away into the distance.

However, in either a stroke of wild luck or fated-to-be, the 1998 24 Hours of Le Mans was anything but a typical race. The Porsches ran flawlessly, while it seemed that every other manufacturer in the GT1 class had upset some racing deity. The BMW V12 LM retired after a wheel bearing failure. The CLK-GTRs suffered oil starvation as there were defects in their oil pumps, spending many laps in the pits. Even the vaunted Toyota GT-ONE, easily the fastest car on track, suffered gearbox issues and had to spend tens of laps in the pits getting them replaced.

This meant that the 911 GT1-98, albeit not slow, but slower than most of the GT1 field, came in first and second overall. This was a milestone win for Porsche, as with 16 overall victories, they became the winningest team at Le Mans in history. That fact alone cemented the 911 GT1-98 into the history books, but it was also a notable race in that the GT1-98 that came in first, driven by Laurent Aiello, Stephane Ortelli, and Allan McNish spent the least amount of time of any manufacturer, including the lower classes, pushed back into the garage. Even then, it was only to allow for brake pad changes to be done quicker with more mechanics on the car.

Of all the 911 GT1’s that were made, we chose the GT1-98 simply because while it was not competitive across the rest of the races of the year, all the planets aligned on the 6th and 7th of June, 1998, and Porsche’s legendary reliability earned them the win. It is also notable as being the only 911 GT1 to quite literally fly, as during the Petit Le Mans at Road Atlanta in October of that year, the #26 GT1-98 was running a high rear downforce setup that pushed the nose up over a crest, allowing air to catch under the body, lifting the car into the air where it did a full backflip, landing on the tail at the start of the second rotation and spearing off into the retaining wall beside the track.

The driver, Yannick Dalmas, was completely fine, a testament to the carbon fiber monocoque construction of the Porsche. In fact, as the 1998 season required homologation versions of the LM-GT1 cars, the now very rare and very collectible 911 GT1 Strassenversion, the road going version of the race car, is lauded as one of the safest homologation specials made in history. A little fun fact, but unless you’re literally a billionaire, you probably won’t ever own one, as they are extremely rare cars that are often the crowning jewel of a collection.

More: Porsche 911 GT1 (race cars), Porsche 911 GT1 (production)

Porsche 936 Spyder

Quite late in 1975, Porsche decided they wanted to participate in the newest prototype class of the FIA World Sportscar Championship in 1976, known as Group 6, and developed the 936 Spyder in just a few months. That meant that Porsche was entering cars in both Group 5 with the 935, and Group 6 with the 936.

This was able to be achieved as the 936 Spyder took a lot of cues from the 908/03 and 917/10 race cars of the previous years, both influences which can be seen in the open cockpit and air snorkel design, and tail section respectively. The car was built as an aluminum tubular frame, covered with a lightweight plastic body. Beneath the massive air snorkel lay a turbo 2.1L flat-six from the 1974 RSR 2.14, modified to output 540 HP.

In pre-season testing in February of 1976, the first race-ready car, named the “black widow” as it used an unpainted black plastic body, stormed around Le Castellet Circuit in France. It surpassed everyone’s expectations, proving to be incredibly stable at high speed, responsive while cornering, and giving the car a good kick up the backside when the loud pedal met the floor.

The 1976 World Sportscar Championship was to consist of 7 races outside of the 24 Hours of Le Mans. With title sponsorship from frequent partner Martini, five 936s under the team name of Martini Racing won 6 of 7 rounds, with the only non-936 win going to a Porsche 908/3 at the first round at the Nurburgring. Even then, that was only because the 936 debuted at the second round at Monza.

The 936 also decimated the field at Le Mans, with Jacky Ickx and Gijs van Lennep taking the overall win. The feat was repeated in 1977 with the 936/77, an evolution of the car that was lighter, shorter, and had a second turbo on the engine to give it 20 more HP. Facing an armada of four Renault Alpine works cars and two Renault factory-supported Mirage teams, Jacky Ickx, Jurgen Barth, and Hurley Haywood put in the performance of their lives, winning overall. The final year the 936 raced, before the next car in our list replaced it, the 936/81 lifted the overall victory trophy one last time at Le Mans.

More: Porsche 936

Porsche 956 C

Group C, the newest class of prototype racing in the FIA World Sportscar Championship, is often considered the peak of unrestricted, all-out racing with few rules and even fewer safety measures. Group C was accompanied by the legendary Group B GT class cars for circuit racing, and Group B Rally for the World Rally Championship, which pushed car development and technology to the absolute limit of what could be done.

Part of this was Porsche’s iconic entry into the class, the incredibly dangerous but extremely fast 956 C. Using ground effects, a shape designed to shove the car into the road anywhere the air touched it, and the shortest cabin of a Porsche since the 917/10, the car was literally a frame and shell around the monster in the middle, a 2.65L twin-turbo flat-six that generated 635 HP. It was also the first time that Porsche had made a prototype car with a full monocoque chassis, out of ultra-lightweight but strong racing-grade aluminum.

The biggest danger in the design, however, was that to give the drivers the best possible view to see everything, their legs and feet were quite literally ahead of the front axle, a flaw that would come back to bite Porsche hard. However, when it ran at the 24 Hours of Le Mans and in the FIA WSC in 1982, it was untouchable. Stuttgart got a full display case worth of trophies over the year, including an overall podium sweep at Le Mans, and the WSC overall trophy.

Customer racing teams were keen to get their hands on the newest, most dominant car from Germany, so in 1983, after a winter season of development, a customer prototype car was created. The 956, and its evolution, the 962, would go on to rule the rest of the decade in Group C racing, winning race after race, either in works or customer teams, but that domination came at a heavy cost.

The 956 C, in the quest to be the fastest, meanest, most dominant car on the grid, was made in a time when safety was starting to become important, but wasn’t quite there yet. As such, drivers that were in 956 C crashes were often injured, sometimes severely, and there are many deaths associated with the car. None of these was more impactful to Porsche than that of Stefan Bellof, a prodigy that had an almost sixth sense about the 956 C and could drive it absolutely on the limit. This resulted in him setting the lap record at the Nurburgring Nordschleife in 1983, 6 minutes and 11.13 seconds, which would only be beaten by another Porsche, the 919 Evo, 35 years later.

However, during the 1985 1,000 KM of Spa-Francorchamps, when Bellof, in a 956 C, tried to make a pass on Jacky Ickx, in a 962 C, a freak incident of side drafting pulled his car into the rear quarter panel of the 962, at one of the fastest parts of the track, the Eau Rouge/Raidillon complex that could be taken nearly flat out in the Porsches. Ickx’s 962 spun and impacted the retaining wall rearwards, saving his life, but Bellof’s 956 C speared head-on into the wall, crushing the entire front of the car up to the firewall between the cockpit and the engine, killing Bellof instantly.

The 956 C was quickly phased out following Bellof’s death, with the 962 C, with its much safer and further back cockpit, becoming the choice of many teams and drivers. However, before that incident, the 956 C was seen as perhaps the greatest race car to ever have been created, a dominant force that few teams knew how to counter, and it won so many races that if you go back and look at the stats of any endurance race between 1982 and 1986, a 956 C was on every podium. Most of those were on the top step, too. Rarely has a race car been so dominant, and thus, the dangerous and fast 956 C earns its place on this list.

More: Porsche 962, Porsche 956

Porsche 908

In the late sixties, Ferdinand Piëch wanted Porsche at the top of motor sports and the 908 was his answer. In facing the best that both Ferrari and Ford could produce, it sparked a new generation of Porsche prototypes that led to their most successful era. For the first time, Porsche competed in all championship races in 1968 with hopes of overall victory. This new era began when the 908 Coupés supported the much smaller 907 midway through that year’s season.

The 908 was the first car built for the Group 6 Prototype class of the World Sportscar Championship. Cars of this type were limited to 3.0L engines, which Porsche managed with a flat-eight engine that produced 350 HP, hence the 908 designation. The car had a stellar debut, but during 1968, several mechanical gremlins caused Ford’s 1968 GT-40 Mk IV to take the title.

Despite this, because of its aluminum space frame, low, sleek body, and superb power-to-weight ratio as it weighed only 1,500 lbs, when the 908 had all of the gremlins worked out, it was enormously successful. It won the 1968 and 1969 Spa-Francorchamps 1000 KM outright, and while it never won a 24 Hours of Le Mans, in three different decades it raced there and placed on the podium.

The 908 had several iterations and evolutions, from the 908/2 and 908/3 of 1969 and 1970 respectively, to the final edition, the 908/3 Spyder Turbo in 1980. Instead of picking just one, we felt it was better to group them up under one heading, as once they were running consistently after that first year, they also helped pave the way for the legendary 917.

More: Porsche 908

Porsche 959 Rally

When the FIA created the Group B Rally class, very few restrictions were placed on the cars. The only real rule was that there had to be homologation versions made, and the cars needed to adhere to a few minimum weight requirements. The rest was left almost completely wide open, which created a “gold rush” of technology and development that quite literally advanced automotive technology tenfold over the course of four years.

Part of that leap was the first true Porsche supercar, the 959. Designed in secret, the car, which was based on a Type 930 911, was given a twin-turbo flat-six engine that mixed water and air cooling, an electronically controlled all-wheel-drive system, on the fly electronically adjustable suspension, some of the first types of tire pressure monitoring systems, and a body that was shaped by some of the earliest uses of computer-simulated aerodynamics (known as Computer Aided Fluid Dynamics Simulation in 2023, or CFD for short).

The 959 Rally was developed by the motorsports department in Weissach, taking the Group B rally car and turning it into a desert storming monster, meant to challenge and win the 1985 Paris-Dakar. This was fortunate, as the original plan, to run the 959 Group B in the FIA World Rally Championship, was curtailed by the FIA’s outright cancellation of the class after multiple spectator and driver/co-driver deaths due to the cars being beyond control.

The 959 Rally participated in the 1985 Paris-Dakar, with three cars entered. Its refinements included a massive 330 liter fuel cell, a full, robust body shell of resin-impregnated fiberglass, a chassis that was light but reinforced for the brutal trials of the Sahara desert, and a robust 6-speed gearbox that was so over-engineered that it looked like it had barely been used after the race.

The 959 placed first, second, and sixth in their outing in 1985, with a Sahara-crossing speed record being set at 242 KPH, or 150 MPH. Keep in mind, while the homologation special 959s, of which 292 units, including the development units, were built, could go much faster on paved surfaces, the 959 Rally’s were reaching that speed on sand. The 959 is legendary in and of itself for being the single most technologically advanced car produced by anyone in the 1980s, but when you realize that three of them were roaring across the open desert at over twice freeway speed, it becomes a near mythical car, and is the perfect way to cap off this list of the greatest race cars that Porsche has made in its lifetime.